SAATUSEAASTA 1944

THE FATEFUL YEAR 1944

EESTI SAATUS TEISES MAAILMASÕJAS

ESTONIA’S FATE IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Koostajad/ Compiled by: Meelis Maripuu, Ülle Kraft, Aivar Niglas

Teine maailmasõda hävitas Eesti riigi ja pillutas laiali meie rahvastiku. Nõukogude Liit okupeeris Eesti 1940. aastal, järgnenud terrori käigus arreteeriti ca 10 000 inimest, teised ca 10 000, raukadest rinnalasteni, küüditati kodumaalt NSV Liitu. Hävitati terved perekonnad, arreteerituist õnnestus pärast sõda kodumaale naasta üksikutel inimestel, küüditatuist hukkusid vähemalt pooled.

The Second World War destroyed the independent Republic of Estonia and scattered its population. The Soviet Union occupied Estonia in 1940. Approximately 10,000 people were arrested in the course of the subsequent terror. About another 10,000 people, from infants to the very elderly, were deported from their Estonian homeland to the Soviet Union. Entire families were destroyed. Only a few of the arrested people managed to return to their homeland after the war. At least half of the deported people survived.

Rahvusvahelist õigust eirates mobiliseeriti 1940–1941 Nõukogude Punaarmeesse ligi 45 000 Eesti kodanikku ning nad kadusid oma perekondade vaateväljast. Osadel õnnestus põgeneda, kuid 6000–8500 meest suri Nõukogude tagalas tööpataljonide ebainimlikes tingimustes, tuhanded vahistati, hukati või jäid sõjas teadmata kadunuks. Ellujäänud naasid Eestisse 1944 okupatsioonivägede koosseisus.

Nearly 45,000 Estonian citizens were mobilised into the Soviet Red Army in 1940–1941 in disregard of international law. They disappeared from the field of view of their families. Some managed to escape, but 6,000 – 8,500 men died in the Soviet rear area in the inhumane conditions of labour battalions. Thousands were arrested, executed, or went missing in the war. The survi-vors returned to Estonia in 1944 in the ranks of the occupying forces.

1941. aasta suvel asendus kommunistlik Nõukogude okupatsioon natsionaalsotsialistliku Saksamaa ülemvõimuga. Võimuvahetus tekitas rahvas esmalt vabanemislootuse, kuid see ei täitunud, ja uue terrori käigus mõrvati 8000 Eesti inimest. Paljud arreteeriti, kahtlustatuna koostöös kommunistidega. Reaktsioonina Nõukogude terrorile astusid sajad eestlased vabatahtlikuna Saksamaa poolel relvateenistusse, soovides kätte maksta ja lootes Venemaale tungides vabastada lähedased. Lisaks hakkas ka uus okupatsioonivõim rahvusvahelist õigust väänates eestlasi oma relvajõududesse mobiliseerima.

In the summer of 1941, the communist Soviet occupation was replaced by that of National Socialist Germany. The change in power initially inspired hope for liberation among the population but that did not materialise. In the course of a new wave of terror, 8,000 Estonian people were murdered. Many were arrested on suspicion of collaboration with communists. Hundreds of Estonians enlisted in the armed services on the side of Germany in reaction to the Soviet terror, with the desire to exact revenge and hoping to free their close relatives by invading Russia. Additionally, the new occupying regime also started mobilising Estonians into its armed forces, thus distorting international law.

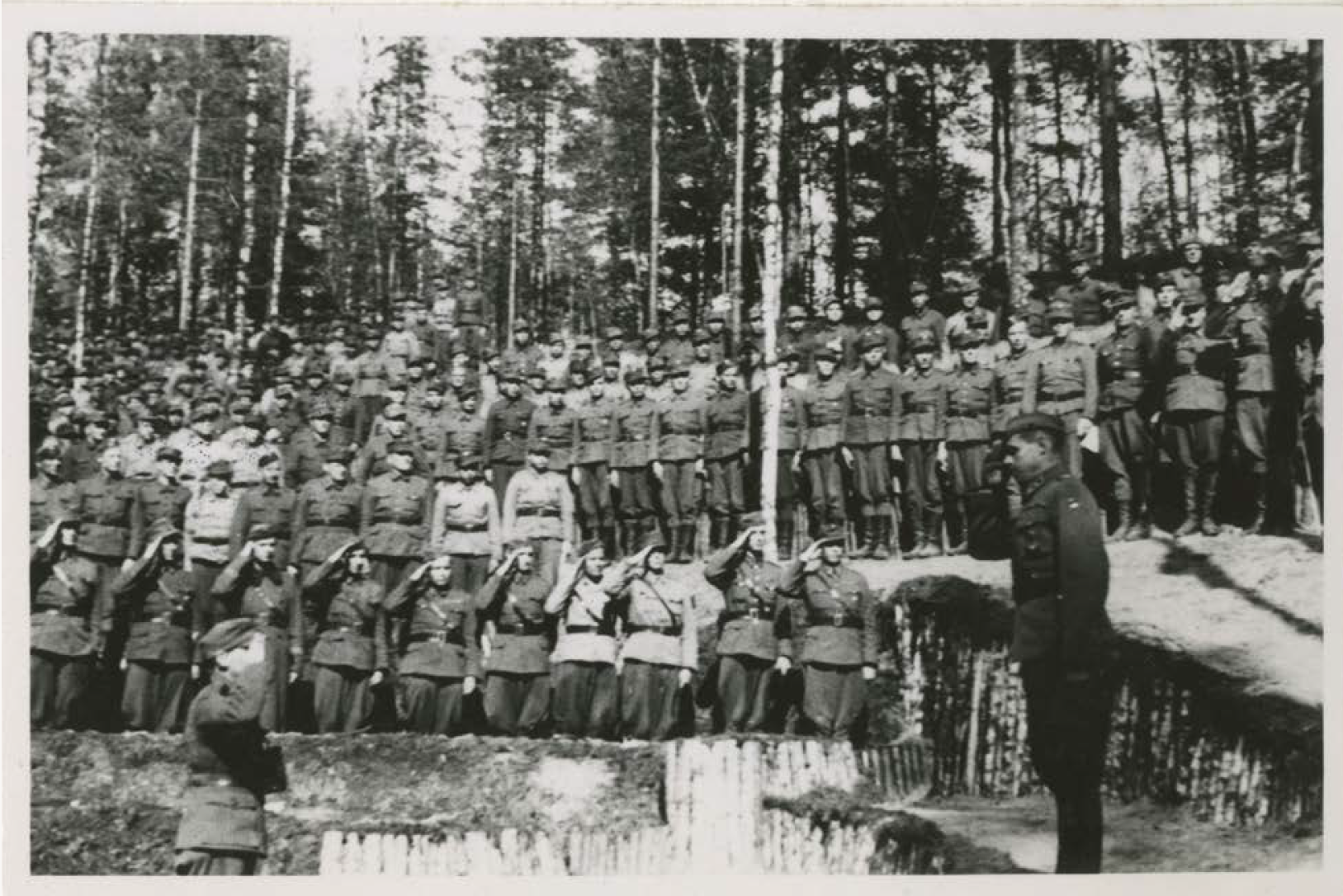

Eestimaa kindralkomissar K. S. Litzmann ja Eesti Omavalitsuse juht Hjalmar Mäe kohtuvad 1942. a Viljandi sõjavangilaagris Punaarmee poolelt üle tulnud eestlastega.

The General Commissar of Estonia K. S. Litzmann and the leader of the Estonian Omavalitsus (Self-Administration) Hjalmar Mäe meet with Estonians who have defected from the side of the Red Army at a prisoner of war camp in Viljandi in 1942.

Illustratsioon / illustration: RA

1943. aastast hakkas eestlaste hulgas levima kartus, et sakslased jätavad Baltikumi maha ja nad jäetakse kommunistide meelevalda. Loodeti, et Saksa võimud võimaldavad eestlastel evakueeruda Saksamaale ning annavad relvi oma piiride kaitseks. Rootsi ja Saksa võimude kokkuleppel lubati enam kui neljal tuhandel Eesti läänerannikul ja saartel elanud eestirootslasel 1943–1944 oma ajaloolisele kodumaale evakueeruda, koos nendega lahkus juba ka hulk eestlasi.

In 1943, the fear started spreading among Estonians that the Germans would abandon the Baltic states and that they would be left at the mercy of the communists. It was hoped that the German authorities would enable Estonians to evacuate to Germany and provide arms for the defence of their borders. The Swedish and German authorities agreed to allow more than four thousand Estonian Swedes living on the western coast and islands of Estonia to evacuate to their historical homeland in 1943–1944. A number of Estonians left together with them.

Sajad mehed ei soovinud kommunismi vastu võidelda Saksa mundris ning põgenesid karmist keelust hoolimata Soome, liitusid sealse armeega ja on saanud tuntuks soomepoiste nime all. Koos meestega põgenes 1943. aastal üle Soome lahe ka hulk naisi ja lapsi, nii et soomlastel tekkis tunne, et kogu Põhja-Eesti rannik jääb inimtühjaks.

Hundreds of men did not want to fight communism in German uniform and regardless of strict prohibition, they fled to Finland, joined the army there, and became known as the soomepoisid (Finnish Boys). A large number of women and children also fled across the Gulf of Finland together with the men in 1943 so that the Finns got the feeling that the entire coast of Northern Estonia would become deserted.

1944. aasta jaanuaris jõudis Punaarmee Narva juures taas Eesti piirideni ja valdav osa linna elanikke evakueeriti, lükates liikuma sisemaise põgenike laine. Hirm naasva punaterrori ees viis osa mehi taas vabatahtlikult Saksa relvateenistusse, teisi kallutas see alluma mobilisatsioonikäsule. Sõja kestel teenis Saksa relvaüksustes kokku ligikaudu 50 000 eestlast.

In January of 1944, the Red Army once again reached Estonia’s borders at Narva and the vast majority of the city’s population was evacuated, starting up a wave of people fleeing within Estonia. Fear of the return of Red Terror caused some men to voluntarily enlist in the German armed forces and

disposed others to obey mobilisation orders. Over the course of the war, a total of roughly 50,000 Estonians served in German armed units.

9.–10. märtsini tabas Tallinna ulatuslik pommirünnak, mis hävitas ligi kolmandiku linna elamispinnast ja sundis paljud perekonnad lahkuma. Suveks valdas inimesi üha kasvav rahutus, mida tõukasid tagant mitmed märgid: Saksa võimuesindajate perekonnad lahkusid ning näiteks Eesti raudteelaste, kes olid sõja seisukohalt väga olulised spetsialistid, perekondadele tehti ettepanek evakueeruda Saksamaale. Samas püüdsid Saksa võimud igati vältida üldise paanika puhkemist. Suvel kestsid lahingud Virumaal Narva ja Sinimägede piirkonnas. Augusti teiseks pooleks oli sõjaline olukord aga kujunenud selliseks, et Saksa võimud alustasid avalikult ettevalmistusi kohalike tsiviilisikute evakueerimiseks, mida käsitleti küll ajutise abinõuna. 16. septembril loobus Saksamaa oma positsioonide kaitsmisest Mandri-Eestis ning alustati oma üksuste evakueerimist. See päästis valla ka eestlaste massilise põgenemise. Septembri lõpuks oli kogu Mandri-Eesti Punaarmee kontrolli all, viimased Saksa üksused taandusid Sõrvest 25. novembril.

An extensive bombing raid was carried out against Tallinn on 9–10 March 1944, which destroyed nearly a third of the city’s residential space and forced many families to leave the city. By the summer, ever-growing unrest gained ground among the people, impelled by many signs: the families of German representatives of state authority departed, and the Germans proposed to the families of Estonian railwaymen, who were key specialists in terms of the war, that they evacuate to Germany. At the same time, the German authorities tried in every respect to prevent the outbreak of general panic. Battles continued in the summer in Viru County in the region of Narva and the Sinimäed. By the latter half of August, the military situation had become such that the German authorities openly launched preparations for evacuating local civilians, which was admittedly considered a temporary measure. On 16 September, Germany abandoned the defence of its positions in continental Estonia and started evacuating its units. That triggered the mass flight of Estonians. At the end of September, all of continental Estonia was under the control of the Red Army. The last German units retreated from Sõrve in Saaremaa on 25 November.

PÕGENEMINE ARVUDES

EXODUS IN NUMBERS

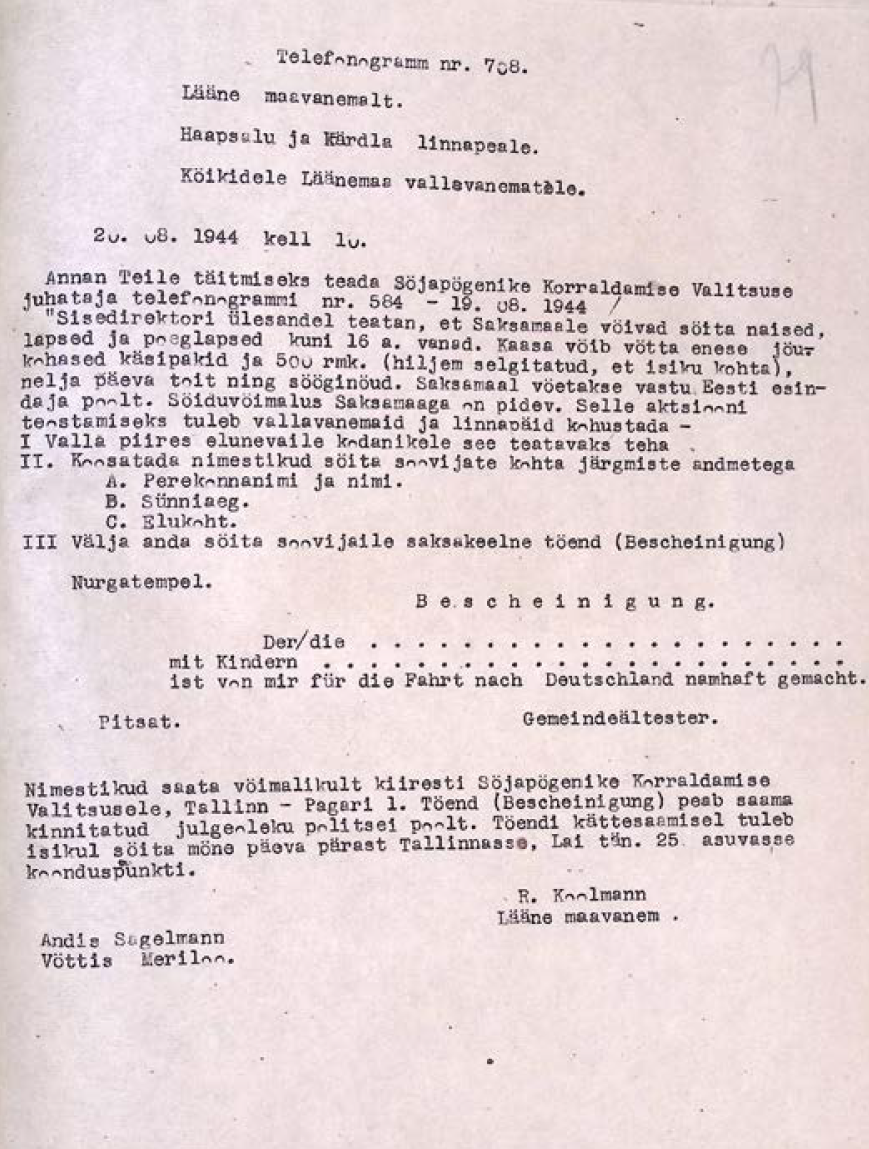

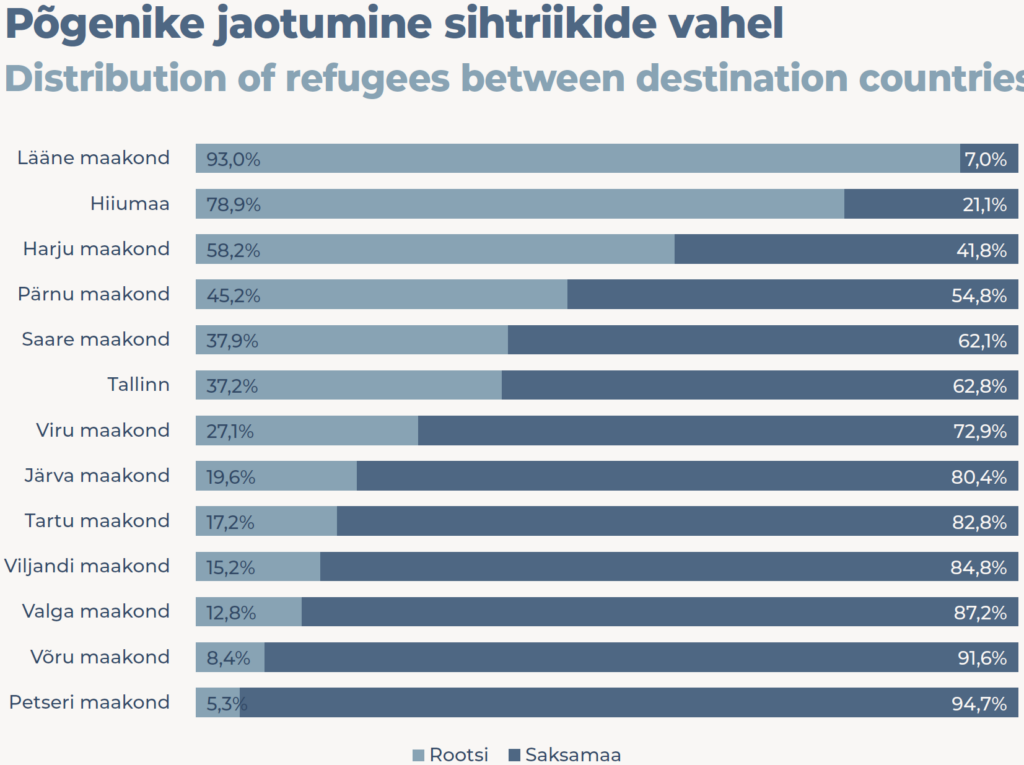

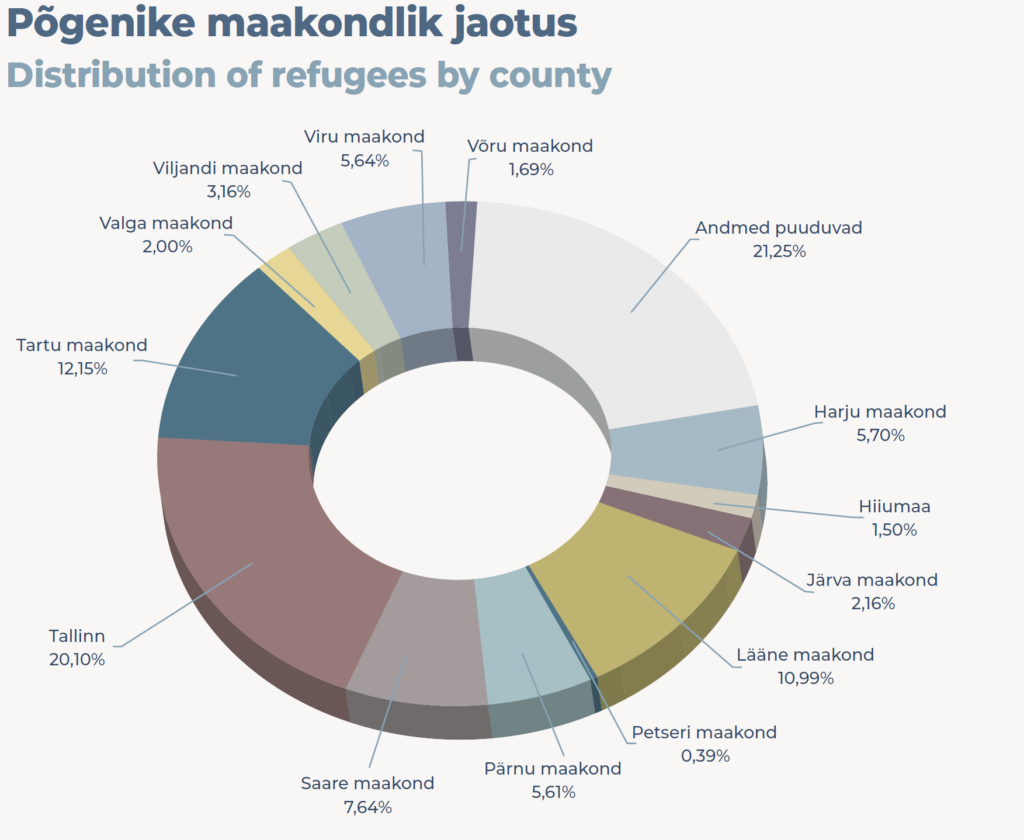

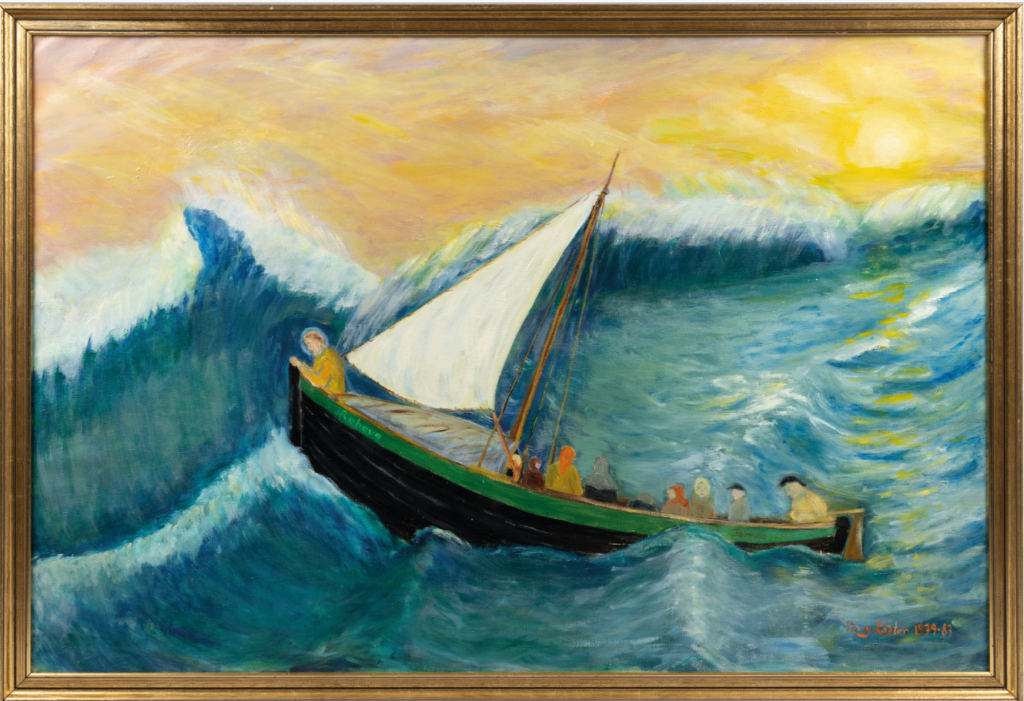

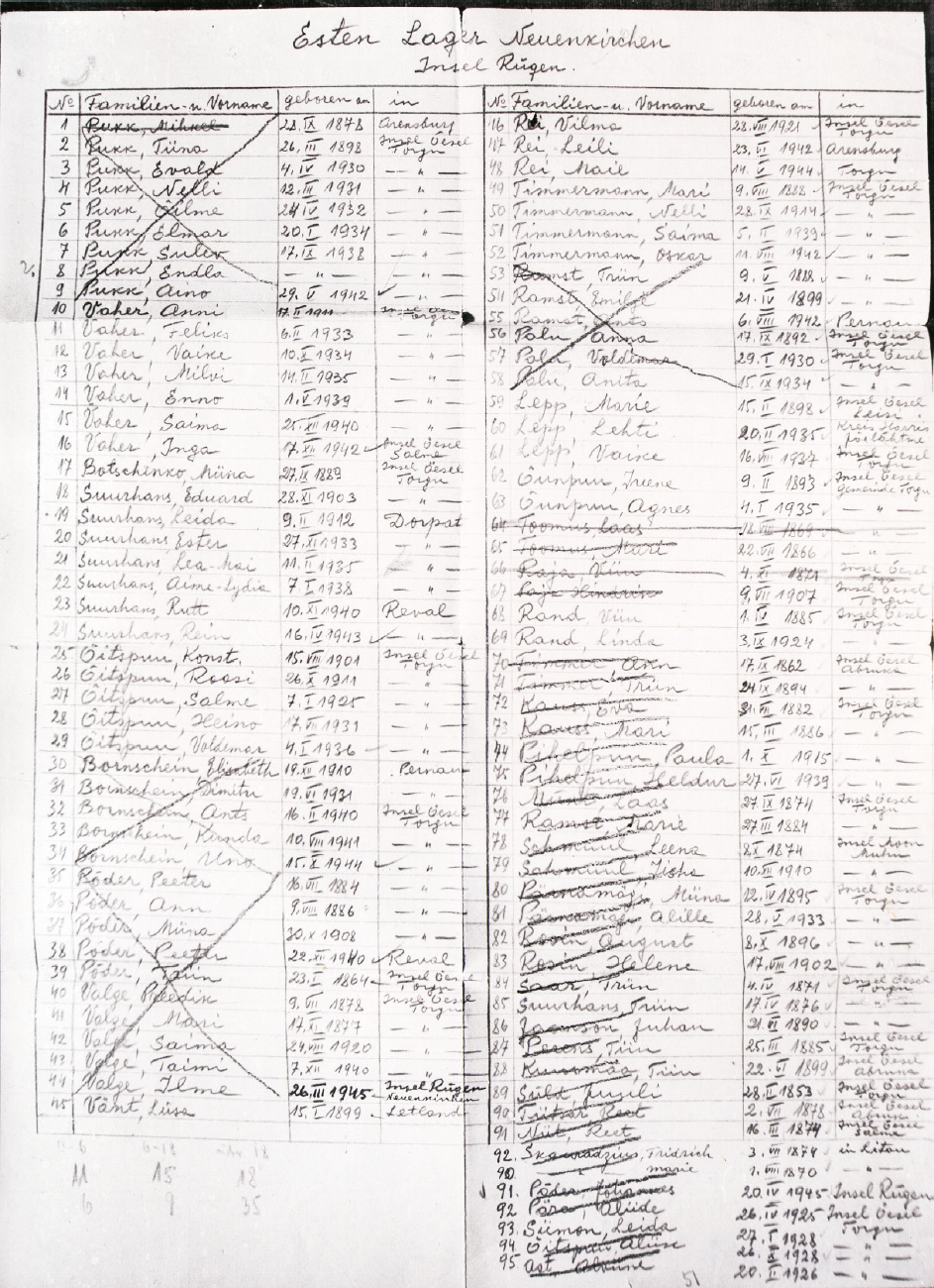

Eesti sõjapõgenikud moodustasid väga eripalgelise seltskonna. Kõige selgepiirilisem osa neist olid enam kui 7000 rannarootslast, kes olid ka ühed esimesed lahkujad. Eestlaste arvukam lahkumine kodumaalt sai alguse 1943. aastal, põhjarannikult Soome. Suurem osa (u 3500) neist olid mehed, kes võeti üle lahe jõudes Soome armee teenistusse. Meeste kõrval lahkus Põhja-Eestist Soome ka vähemalt 500 naist ja last, kes olid 1944. aasta sügisel sunnitud Nõukogude Liidule väljaandmise kartuses edasi põgenema Rootsi. Koos sõja lõpufaasi põgenikega jõudis Soome kaudu Rootsi vähemalt 5000–7000 Eesti sõjapõgenikku. Massiline põgenemine Eestist algas 1944. aasta augustis ning kestis kuni oktoobri alguseni, mil ka Saaremaa rannik langes valdavas osas Punaarmee kontrolli alla. Sõjapõgenike kaks esmast sihtriiki oli Rootsi ja Saksamaa. Põgenemise kõrghetk mõlemas suunas jäi septembri teise poolde, mil omakäeline põgenikevool suundus kõikmõeldavatel meresõidukitel Rootsi suunas ja Saksa laevastik korraldas Tallinna evakueerimise.

Senistel andmetel oli esimestel sõjajärgsetel aastatel peamiselt Saksamaal ja Rootsis kokku ligi 80 000 Eesti elanikku.

Estonian war refugees as a whole represented a diverse cross-section of society. The most clearly defined group among them was the more than 7,000 coastal Swedes, who were also among the first to leave. The largest wave of departures of Estonians from their homeland began in 1943 from Estonia’s northern coast to Finland. The greater portion of these particular refugees (about 3,500) were men who were accepted to serve in the Finnish Army when they arrived on the other side of the gulf. Alongside men, at least 500 women and children also left Northern Estonia for Finland. In the autumn of 1944, they were forced to flee onward to Sweden due to fears of being extradited to the Soviet Union. Together with refugees from the last phase of the war, at least 5,000–7,000 Estonian war refugees

reached Sweden via Finland. Mass exodus from Estonia began in August of 1944 and lasted until the start of October when the Red Army gained control of most of the coast of Saaremaa. Germany and Sweden became the two primary destination countries for the war refugees. The latter half of September was the high point of the exodus in both directions. That is when the German fleet organised evacuation from Tallinn, and a flood of refugees fleeing on their own headed for Sweden on board all manner of seagoing vessels. According to hitherto available information, nearly 80,000 Estonians in total lived abroad in the first postwar years, most of them in Germany and Sweden.

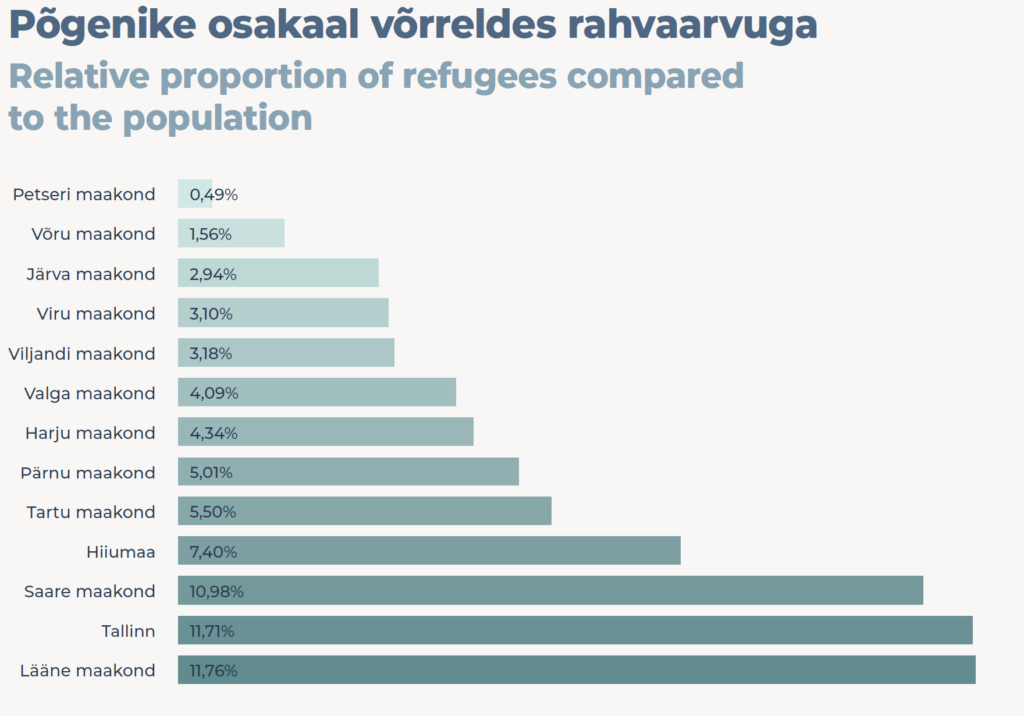

Järgnev ülevaade tugineb ligi 65 000 põgeniku andmetel, kelle isikuandmed koos varasema elukohaga on õnnestunud seni kindlaks teha. Lahknevana toonasest haldusjaotusest, on ülevaatlikkuse huvides Tallinna elanikud eraldatud Harjumaast ning Hiiumaa vallad on eraldatud Läänemaast.

The following overview is based on data concerning nearly 65,000 refugees, whose personal data has hitherto been ascertained together with their previous places of residence. In divergence from the administrative divisions of that time, residents of Tallinn have been separated from Harju County and the rural municipalities of Hiiumaa have been separated from Lääne County in the interests of comprehensiveness.

Saksamaa eri paigus oli sõja lõpus vähemalt 37 000 ja enam eestlast (ligi 60% Eesti põgenikest). Kahe suurema grupina tõusevad esile tsiviilisikud, keda Saksa võimud evakueerisid meritsi suurtel laevadel, ning eesti mehed, kes olid Saksa relvaüksuste koosseisus taandunud Saksamaale. Arvuliselt väiksem osa, üle 26 000 (üle 40%) põgeniku jõudis Rootsi. Nende hulgas oli enamik rannarootslastest üle mere pääsenud Saksa võimude loal, kuid ülejäänud põgenikud pidid trotsima okupatsioonivõimude keelde ning tormist merd. Kuigi Rootsi oli põgenike enamuse eelistatuim sihtriik, ei olnud rannikust kaugemal elavatel inimestel lihtne leida kohta salaja lahkuvatel paatidel. Suurem võimalus Rootsi pääseda oli rannarahval. Saaremaa puhul on Saksamaa suurem osakaal tingitud statistikas kajastuva ca 2500 sõrulase sunniviisilisest evakueerimisest Saksamaale.

There were at least 37,000 Estonians (nearly 60% of Estonian refugees) in various parts of Germany at the end of the war. Two sizable groups that emerge are civilians who the German authorities evacuated by sea on board large ships, and Estonian men who had retreated to Germany in the ranks of German armed units. A numerically smaller portion of refugees, more than 26,000 (over 40%), reached Sweden. Among them were most of the coastal Swedes, who crossed the sea with the permission of the German authorities. The rest of the refugees had to defy the bans of the occupying authorities and brave the stormy sea. Although Sweden was the most preferred destination country for the majority of the refugees, it was not easy for people living farther from the coast to find places for themselves in boats that departed secretly. People living on the coast had a better chance to get to Sweden. The greater relative proportion of refugees that went to Germany in the case of refugees from Saaremaa is due to the forced evacuation to Germany of approximately 2,500 inhabitants of Sõrve, which is reflected in the statistics.

Arvuliselt suurim hulk põgenikke lahkus Tallinnast, mis on seletatav suurema rahvaarvu ning suhtelise lihtsusega lahkuda Saksa evakuatsioonilaevadega. Järgneb suuruselt teine Eesti linn Tartu koos Tartu maakonnaga ning seejärel loogiliselt saared ning Lääne-Eesti rannik. Läänemaa põgenike suhteliselt suurema arvu põhjus on selgelt pea kogu rannarootsi rahvusrühma lahkumine Eestist.

The numerically largest quantity of refugees left from Tallinn, which can be explained by the city’s larger population and the relative ease with which people could depart on board German evacuation ships. The second largest number of refugees went from Tartu, Estonia’s second city in terms of size, together with Tartu County, followed thereafter logically by the islands and the Western Estonian coast. The reason for the relatively larger number of refugees from Lääne County is clearly the departure of almost the entire coastal Swedish ethnic group from Estonia.

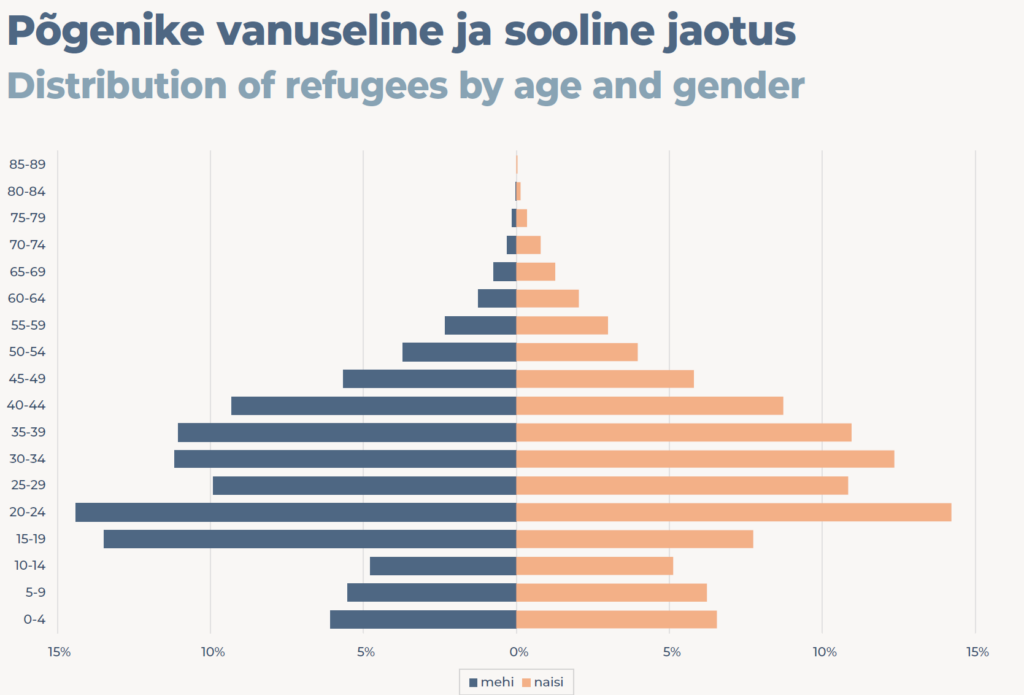

Põgenike soolise ja vanuselise esmase jaotuse puhul saab esile tuua ühe kõrvalekalde. Silma torkab 15–20-aastaste meeste suurem osakaal samas vanuses naistega võrreldes, mida saab selgitada Saksa relvateenistuses olnud noormeeste proportsionaalselt suurema lahkumisega kodumaalt. Vahetult pärast sõda pöördus erinevatel põhjustel Eestisse tagasi vähemalt 10 000 sõjasündmuste käigus kodumaalt lahkunud inimest. Enamasti võis see olla seotud perekondlike põhjustega, kuid oma roll oli ka Nõukogude propagandal. Valdav osa põgenikest ei pidanud naasmist NSV Liidu okupeeritud Eestisse võimalikuks ja jäid läände, lootes esialgu Eesti kiiret vabanemist. Rahvusvaheline olukord seda aga ei võimaldanud ja eelkõige Saksamaal olijad pidid endale leidma uue elupaiga muudes riikides. Eestlaste suurimad kogukonnad moodustusid Rootsis, Kanadas, Ameerika Ühendriikides, Austraalias ja Suurbritannias.

A deviation can be highlighted regarding the primary distribution of refugees by gender and age. The larger relative proportion of men aged 15–20 years compared to women in the same age range stands out. This can be explained by the proportionally larger rate of departure from the homeland of young men who were serving in the German armed forces. Immediately after the war, at least 10,000 people who had left their homeland in the course of the events of the war returned to Estonia for various reasons. For the most part, that could be connected with familial reasons, but Soviet propaganda also had its role. The vast majority of refugees did not consider it possible to return to Estonia while it was occupied by the Soviet Union. They remained in the West, initially hoping for the quick liberation of Estonia. The international situation, however, did not allow that. The Estonians in Germany largely had to find new places of residence for themselves in other countries. The largest communities of Estonians took shape in Sweden, Canada, the United States, Australia, and Great Britain.

Võrreldes sõjaeelse rahvaarvuga, oli põgenike osakaal rahvastikust suurim Läänemaal, mis on taas seotud rannarootsi kogukonna lahkumisega Rootsi. Pea sama suur osa elanikest põgenes ka Tallinnast, mida võimaldas suures osas Saksa võimude korraldatud evakueerimisaktsioon 16.–22. septembrini. Järgneb Saare maakond, kus põgenike osakaal on graafikul kujutatust eelduslikult mõnevõrra suurem, kuid puudulikud elukoha andmed ei ole võimaldanud seda veel tuvastada. Proportsionaalselt suurem peaks olema ka Virumaa põgenike osa, kuid puudulike elukoha andmete tõttu ei ole sedagi veel fikseeritud.

Compared to the prewar population, the proportion of refugees relative to the population was the largest in Lääne County, which is once again due to the departure to Sweden of the coastal Swedish community. Almost just as large a part of the population also fled from Tallinn. The evacuation operation organised by the German authorities from 16 to 22 September largely enabled this. The next largest proportion is from Saare County, where the relative proportion of refugees is presumably somewhat larger than that depicted in the graph. Deficient data on places of residence has not allowed this to be ascertained yet. The share of refugees from Viru County should also be proportionally larger but this too has not yet been ascertained due to deficient data on places of residence.

VIRUMAA

PÕGENEMINE SOOME

ESCAPE TO FINLAND

Koostaja/Compiled by: Uno Trumm

Pärast Stalingradi lahingus lüüa saamist 1943. aasta kevadtalvel ja sellele järgnevat ebaedu Idarindel, kasvas Saksa armee vajadus sõdurite järele. 1943. aastal viidi Eestis läbi 1920.–1924. aastal sündinud meeste mobilisatsioon Eesti Leegioni. See tõi kaasa mobilisatsiooniealiste meeste põgenemise üle lahe Soome. Koha paati sai osta raha, kulla vm väärtusliku eest ning põgenikke vedasid üle lahe endised Soome ja Eesti randade salapiirituse ja -kauba vedajad.

After suffering defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad in the winter and spring of 1943, and the setbacks that followed it on the Eastern Front, the German Army’s need for soldiers increased. A mobilisation of men born from 1920 to 1924 into the Estonian Legion was carried out in 1943. This led men of mobilisation age to flee across the gulf to Finland. One could buy one’s place in a boat in return for money, gold, or other valuables. Former contrabandists and smugglers of spirits on the coasts of Finland and Estonia took refugees across the gulf.

Meeste kogunemine oli määratud õhtule, kella kaheksaks Altja Uustalu karjamaa nurgale tihedasse kuusepõõsastikku. Saabusin sinna pimedas. Mehi kogunes salkkond, umbes kolmekümne ümber. Alustasime kaasavõetud pampudega matka läbi metsa Pedassaare poole. Jõudsime neeme otsale, kuhu pidi tulema paat teatud aal. Ootasime sääl ja andsime kokku lepitud signaale, kuid merelt ei tulnud mingit vastust. Hommikupoole ööd pöörasime kodu poole tagasi, et mitte kahtlust äratada. Iga mees oli hommikul jälle oma töö juures tagasi, nii ei võinud keegi arvata, missugused seiklused olid meil öösel. Käisime niimoodi kolmel ööl Pedassaare neemel paati ootamas, kuid jällegi tuli meil tagasi pöörduda. Viimaks ei jäänud muud üle, kui uus paat muretseda ja väiksema salgaga üle mere minna. Kaugemalt mehed, Eismalt ja Rutjalt, lahkusid tagasi oma kodudesse, järele jäi Altjalt, Mustojalt ja Vergist kokku üksteist meest. Saime Sepa Eduga kokkuleppele, ta muretses paadi ja sõit läks lahti Pedassaare otsast mardilaupäeva õhtul 1943. Puhus tugev edelatuul – mida kaugemale maast jõudsime, seda suuremaks tõusis lainetus. Kella ühe ajal öösel vilkus ees Byrti majaka tuli. Meil ei olnud suure mastaabiga merekaarti, nii oli väga raske pimedas orienteeruda. Panime mootori seisma ja jäime ootama päevavalget. Suur laine peksis üle paadi ja tegi meid läbimärjaks. Kartsime, et laine lööb paadi vett täis ja sellega meie reis oleks lõppenud õnnetult. Olime varustatud suure õlitagavaraga, kasutasime seda mere vaigistamiseks: mõlemalt pardalt tilgutasime õlis immutatud kottidest õli merre, õli tegi laine ümmarguseks ja paat töötas lainetes hästi. Niimoodi loksusime merel mitu tundi, kuni viimaks koitis päevavalgus. Pöörasime paadiotsa alla lainet ja tüürisime lainemurrust saarestiku vahele. Eespool nägime üht saarenukki, kavatsesime selle taha pöörata, et asula lähedale randuda. Nägime paremal ühte asulat, pöörasime paadi selles suunas ja umbes veerand tunni möödudes randusime Sauna saarel. Olime läbimärjad ja tublisti külmetanud. Lahke ja vastutulelik saarerahvas kostitas meid kuuma teega. Õnn oli, et pöördusime sellele saarele, edasi sõites oleksime jõudnud otse sakslaste vaatluspunkti. Saanud endid enam-vähem korraldatud, keha soojendatud ja tujugi tõstetud Eestist kaasa toodud lepikuliisu abil, jätkasime sõitu lähimasse Soome piirivalvepunkti. Meie edasine käekäik jäi Soome võimude otsustada.

Valdek Kaasik. Tõestisündinud lood. Viitna, 2006

The men agreed to gather at eight o’clock in the evening in a spruce thicket in the corner of the pasture of Uustalu farm in Altja. I arrived there in the dark. A group of around thirty men gathered. We set out on our hike through the woods towards Pedassaare with the bags we had brought with us. We reached the end of the cape, where a boat was supposed to come at an agreed time. We waited there and gave the agreed signals, but no reply came from the sea. Towards morning we headed back towards home so as not to arouse suspicion. Each man was back at his job again in the morning. That way nobody could guess what kinds of adventures we had had at night. We went like that to the cape at Pedassaare on three successive nights to wait for the boat, but each time we had to go back home again. We were finally left with no choice but to get another boat and cross the sea in a smaller group. The men from Eisma and Rutja farther away went back to their homes. A total of 11 men remained from Altja, Mustoja, and Vergi. We struck a bargain with Sepa Edu. He acquired a boat and we set off from the tip of Pedassaare in the evening on the eve of Martinmas, 1943. A strong southwester was blowing – the farther we got from shore, the bigger the waves were. At one o’clock at night, the light of the Byrt lighthouse flashed in front of us. We did not have a large-scale navigational chart, so it was really hard to get oriented in the dark. We cut the motor and waited for daylight. A big wave washed over the boat and soaked us. We were afraid that a wave would fill our boat with water. If that happened, our voyage would have ended fatally. We had a large supply of oil. We used it to calm the sea: we dripped oil from bags soaked in oil into the sea on both sides of the boat. The oil rounded off the waves and the boat worked well in the waves. We floated like that on the sea for several hours until daylight finally broke. We turned the front of the boat down the waves and steered between the archipelago out of the breaking waves. Ahead we saw the tip of an island. We planned to turn behind it so that we could land near the settlement. We saw a settlement on the right. We turned the boat in that direction and about a quarter of an hour later, we landed on Sauna Island. We were soaked and cold. The kind-hearted and obliging islanders gave us hot tea. It was lucky for us that we turned onto that island. If we had proceeded onward, we would have headed straight to a German observation post. When we had more or less recovered, warmed ourselves up, and even improved our mood with moonshine we had brought along from Estonia, we continued on our way to the closest Finnish border guard post. It was up to the Finnish authorities to decide our subsequent fate.

Valdek Kaasik. Tõestisündinud lood. Viitna 2006

1943.–1944. aastal ületas pagenute arv 5000 piiri. Neist vähemalt 2 ⁄3 olid noored mehed, kes astusid vabatahtlikult Soome armeesse ja teenisid 8. veebruaril 1944 moodustatud 200. jalaväerügemendis (JR 200), aga ka mereväes ning kaugluures. Augustis 1944 anti soomepoistele ametlikult luba Eestisse tagasi pöörduda, et osaleda kaitselahingutes pealetungiva Punaarmee väeosade vastu. 19. augustil jõudsidki 1628 meest Eestisse tagasi ning osa neist võitlesid Punaarmeega Emajõel.

The number of escapees in 1943–1944 exceeded 5000. At least ⅔ of them were young men who voluntarily joined the Finnish army and served in the 200th Infantry Regiment (JR 200), formed on February 8, 1944, as well as in the navy and long-range reconnaissance. In August 1944, the Finnish boys were officially allowed to return to Estonia to participate in the defensive battles against the advancing Red Army units. On August 19, 1628 men returned to Estonia, and some of them fought against the Red Army at the Emajõgi River.

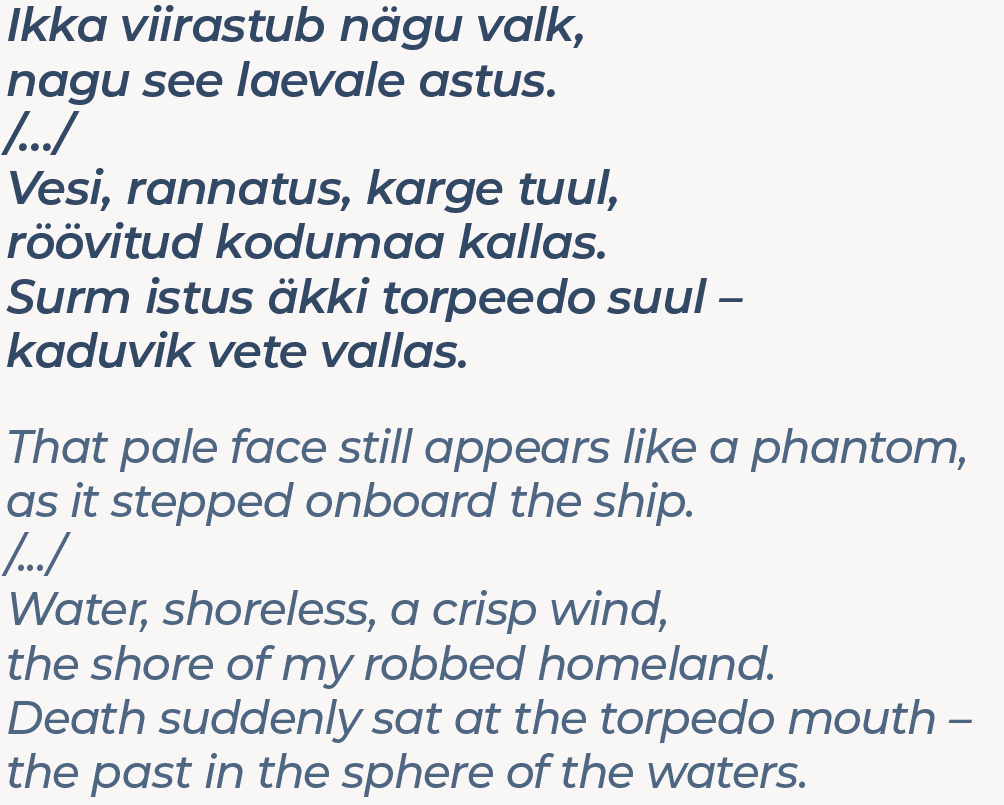

PÕGENEMINE ROOTSI

ESCAPE TO SWEDEN

Hilissuvel 1944 otsustas Saksa armee juhatus loovutada Baltikumi. Narva rinde peajõud alustasid tagasitõmbumist 18. septembri õhtul. Saanud teada Eesti maha jätmisest, põgenesid paljud Rakvere ja Tapa ümbruskonna inimesed ning Viru- ja Harjumaa rannarahvas Soome. 19. septembril jõustunud NSV Liidu ja Soome vaherahulepingus oli klausel, mille kohaselt pidi Soome pool NSV Liidule välja andma kõik „NSV Liidu kodanikud“, kelle hulka loeti ka eestlased. Pärast lepingu jõustumist soovitasidki Soome ametivõimud Eesti Vabariigi kodanikel lahkuda Rootsi. Seetõttu suunaski Soome rannavalve Eestist saabunud põgenikud Botnia lahele Rauma sadamasse, mis oli määratud põgenike kogunemiskohaks. Ühtekokku jõudis Soome kaudu Rootsi umbes 7000 eestlast.

In the late summer of 1944, German Army Command decided to withdraw from the Baltic region. The main forces along the Narva Front started withdrawing in the evening of 18 September. When they found out that Estonia was being abandoned, many people from the vicinity of Rakvere and Tapa, and coastal dwellers in Viru and Harju counties fled to Finland. The armistice agreement between Finland and the Soviet Union that went into effect on 19 September contained a clause according to which the Finnish side had to extradite all ‘Soviet citizens’ to the Soviet Union. Estonians were considered Soviet citizens. After the agreement went into effect, the Finnish authorities recommended that citizens of the Republic of Estonia leave for Sweden. For that reason, the Finnish coast guard sent refugees arriving from Estonia to Rauma harbour in the Gulf of Bothnia, which was designated as a place for gathering refugees together. A total of about 7,000 Estonians reached Sweden via Finland.

Oma põgenemist Võsult Soome kaudu Rootsi kirjeldas Palmse vallavanem Karl Leemet.

21.09. Neljapäev. […] Loksa lahel oli kõva laine küljelt, mis viis ära paadi ankru ja presendi. Jõudsime kella 5 aegu hommikul Leesile, kus olime terve päeva. Õhtul kell 8 läks sõiduks. Jumindal pidime teistega kohtuma, kohtusime kuue paadiga, kus selgus, et keegi ei soovi ees sõita. Nüüd lendasid meist üle Vene lennukid ja varsti algas Tallinna pommitamine, mis võttis meiegi kohal mere valgeks. Kartes, et lennukid võivad meid näha, pöörasime teistest ära ja võtsime kursi Põhjanaelale, sest mingisugust merekaarti meil polnud.

22.09. Reede. Jõudsime kell 4 hommikul Soome randa Biske kohale, nagu hiljem selgus. Ootasime valgenemist ja sõit läks edasi saarte vahel, kus ühel saarel maandusime. Pakkusime peremehele Viru „Spirtu“ ja peremees kutsus kohvile. Hiljem kogunes ka teisi paate ja sõit läks edasi tolli hoone. Sinna oli neid kogunenud ca 20 paadi ümber ja neid tuli järjest juurde. Siis võeti õhtu eel paadid puksiiri poolt sleppi ja toodi Jollasesse, sääl selgus, et Soome valitsus meid Soome ei saa jätta.

23.09. Laupäev. Ööbisime lageda taeva all. Ka siin oli palju tuttavaid. Õhtu eel viisid autod kraami ja inimesed Herttoneemi jaama. Õhtul kell 8 algas siit sõit Rauma suunas. Sattusin kaubavagunisse oma valla inimestega.

24.09. Pühapäev. Võtsime vastu pühapäeva Häämenlinna kohal. Tampere linnas anti meile süüa. Jõudsime kell 9 õhtul Vuojoki raudteejaama, kus ööbisime vagunites.

25.09. Esmaspäev. Käisime kaks kilomeetrit eemal olevas koolimajas söömas. Kell 12 lahkusime Rauma suunas, kuhu jõudsime kl 12, sealt saime autodel kuidagi edasi ja laevale. Laeva minnes kukkusin merre. Laev oli viimse võimaluseni täis kiilutud. Laevas olles väänasin vee välja riietest ja sokkidest, nii kui see mul vähegi võimalik oli. Võtsin taskust viinapudeli, et viina läbi vähegi sooja saada. Perekonnad asetati laevaruumi, kuna teised jäeti tekile. Tuul muutub järjest valjemaks ja tuleb ka vihma. Istun luugi äärele, sest ruumist tuleb väheke sooja üles. Laeva nimi on „Veenus“, Rauma mootorlaev.

Villu Jahilo. Kone punkrist 1945.

I. Käsikiri Ilumäe külamuuseumi valduses.

Karl Leemet, the mayor of Palmse Rural Municipality, described his escape

from Võsu via Finland to Sweden:

21 September. Thursday. […] There were high waves from the side in Loksa Bay that washed away the boat’s anchor and canvas. We reached Leesi at about 5 in the morning and we spent the whole day there. We set out in the evening at 8 o’clock. We were supposed to meet up with the others at Juminda. We met with six boats. It turned out that nobody wanted to be the lead boat. Now Russian planes flew over us and soon they started bombing Tallinn, causing white foam on the sea even at our location. We were afraid that the planes would see us and so we turned away from the others and set our course for the North Star because we had no navigational chart.

22 September. Friday. As it later turned out, we reached Biske on the Finnish coast at 4 in the morning. We waited for daylight and then we continued between the islands. We landed on one of the islands. We offered the man of the house Viru spirits, and he invited us in for coffee. Other boats also gathered later, and we all proceeded to the customs building. Around 20 boats had gathered there, and more boats kept coming. Then, before evening, a tugboat took the boats in tow and brought them to Jollas. There

it turned out that the Finnish government could not let us enter Finland.

23 September. Saturday. We spent the night under the open sky. There were many acquaintances here as well. Before evening, automobiles took belongings and people to Herttoniemi station. We set out from here at 8 in the evening for Rauma. I ended up in a freight car with people from my own rural municipality.

24 September. Sunday. We spent Sunday in Hämeenlinna. We were fed in Tampere. We arrived at Vuojoki railway station at 9 o’clock in the evening where we spent the night in railcars.

25 September. Monday. We went to eat at a schoolhouse two kilometres away. At 12 o’clock we left for Rauma, where we arrived at 12. From there we were taken by automobile onward to the ship. I fell into the sea as I was boarding the ship. The ship was overcrowded. On board the ship I wrung the water out of my clothes and socks as much as possible. I took a bottle of vodka from my pocket and drank some of it to warm myself up a bit. Families were placed in the ship’s hold while the other passengers were left on the deck. The wind grew ever stronger, and it started raining as well. I sat by the hatch because there a little bit of warmth came up from the hold. The name of the ship was Venus, a Rauma motor ship.

Villu Jahilo. Kone punkrist 1945.

I. Manuscript in the possession of Ilumäe Village Museum.

Eesti põgenikega mootorlaeva „Venuse“ tüür oli purunenud ja laev triivis juhitamatult Botnia rannikukaljude suunas. Õnnekombel sattus merehädalistele peale Rootsi rannakaitselaev ja nii jõudis mootorlaev „Venus“, pardal 842 Eesti sõjapõgenikku, Soomest Rauma sadamast Rootsi Örnsköldsviki sadamasse 27. septembril 1944, pärast kaks ööpäeva kestnud triivimist tormisel merel. Pääsenute hulgas oli ka tsiteeritud päeviku autor Karl Leemet.

The rudder of the motorship Venus was broken. It was transporting Estonian refugees. The ship drifted uncontrollably in the direction of the coastal cliffs of Bothnia. Fortunately, a Swedish coast guard ship chanced upon the castaways. Thus, 842 Estonian war refugees on board the motor ship Venus went from Rauma harbour in Finland and arrived at Örnsköldsvik harbour on 27 September 1944 after drifting on the stormy sea for two days and nights. Karl Leemet, the author of the diary quoted above, was among the people who were rescued.

Illustratsioon / illustration: RA

VIIMSI JA SAARED

VIIMSI AND THE ISLANDS

Koostaja/Compiled by: Külvi Kuusk, Kadri Metsaots

Nõukogude okupatsioon muutis rannakalurite elu kardinaalselt. Rannad suleti Nõukogude piiritsooni, kalapüügile kehtestati piirangud, suuremad paadid konfiskeeriti. 1941. aastal mobiliseeriti Viimsist 111 meest Punaarmeesse. Saksa okupatsiooni ajal läks kalurite elu vabamaks, kuid peatselt algas mobilisatsioon Saksa sõjaväkke. Viimsis järgnes kutsele 19 meest, vähemalt 43 põgenes aga üle lahe ja liitus Soome armeega. 1944. aasta suve lõpul põgenes Viimsi küladest üle mere rohkem kui 200 inimest.

The Soviet occupation radically changed the lives of coastal fishermen.

The coasts were sealed off as part of the Soviet border zone. Restrictions were established on fi shing. The larger boats were confiscated. In 1941, 111 men from Viimsi were mobilised into the Red Army. Restrictions on the lives of fishermen were eased during the German occupation, yet mobilisation into the German Army soon began. In Viimsi, 19 men obeyed the mobilisation order but at least 43 fled across the Gulf of Finland and enlisted in the Finnish Army. At the end of the summer of 1944, more than 200 people from Viimsi hamlets fled across the sea.

Merre paigaldatud miinivõrk, veepinnal on nähtaval ujukid. Naissaare põhjarannikult põgenejad pidid arvestama vees varitsevate ohtudega nagu meremiinid, allveelaevade püünised jm.

Network of mines laid in the sea. People who fled from the northern shore of Naissaar had to account for dangers lurking in the water such as sea mines, anti-submarine nets, and other such dangers. Floats are visible on the water surface.

Illustratsioon / illustration: RRM

NAISSAAR / NARGÖ

1939. aastal elas Naissaarel ca 250 eesti ja rootsi rahvusest elanikku. Juunikuus 1940 saabusid saarele Nõukogude sõjaväelased ja 10. juulil teatati, et kohalikud elanikud peavad kümne päeva jooksul kodusaarelt lahkuma. Enamik peresid läks Tallinna ning Kakumäe ja Viimsi rannaküladesse, 14 inimest põgenes kolme kalapaadiga Soome kaudu Stockholmi. Naissaar muudeti tervikuna Nõukogude sõjaväebaasiks.

Oktoobris 1941, kui Nõukogude okupatsioon oli asendunud Saksa ülemvõimuga, lubati elanikel saarele tagasi tulla, kuid merre paigaldatud

miinivõrk muutis kalapüügi riskantseks. Lisaks sakslastele paiknes sõja ajal saarel ka nende liitlaste Soome 16-liikmeline merevaatluspost. 1943. aasta sügisel hakkasid perekonnad Saksa mobilisatsioonist hoidumiseks põgenema. Oma valvekordade ajal aitasid soomlased kohalikel Rootsi sõjapakku põgeneda. Kooliõpetaja Erik Schmidt riputas kooli uksele kirja „Läksin linna kartuleid tooma“. Tegelikult oli ta saanud mobilisatsioonikäsu ja põgenes 19. oktoobril kogu perega Rootsi.

In 1939, about 250 residents of Estonian and Swedish nationalities lived on Naissaar Island. Soviet military personnel arrived on the island in June of 1940. It was announced on 10 July that the local residents had to leave their home island in ten days. Most of the families went to Tallinn and the coastal villages of Kakumäe and Viimsi. Fourteen people fled to Stockholm via Finland in three fishing boats. The whole of Naissaar was turned into a Soviet military base.

In October of 1941, when the Soviet occupation had been replaced by German rule, the islanders were allowed to return to the island but the network of mines that had been laid in the sea made fishing a risky venture.

In addition to the Germans, their ally Finland had a 16-member marine observation station on the island during the war. In the autumn of 1943, families started fleeing in order to evade the German mobilisation. On their watch, the Finns helped locals to flee to Sweden to find refuge from war.

The schoolteacher Erik Schmidt hung a sign on the school door that read ‘Gone to town to buy potatoes’. He had actually received a mobilisation order and fled with his entire family to Sweden on 19 October.

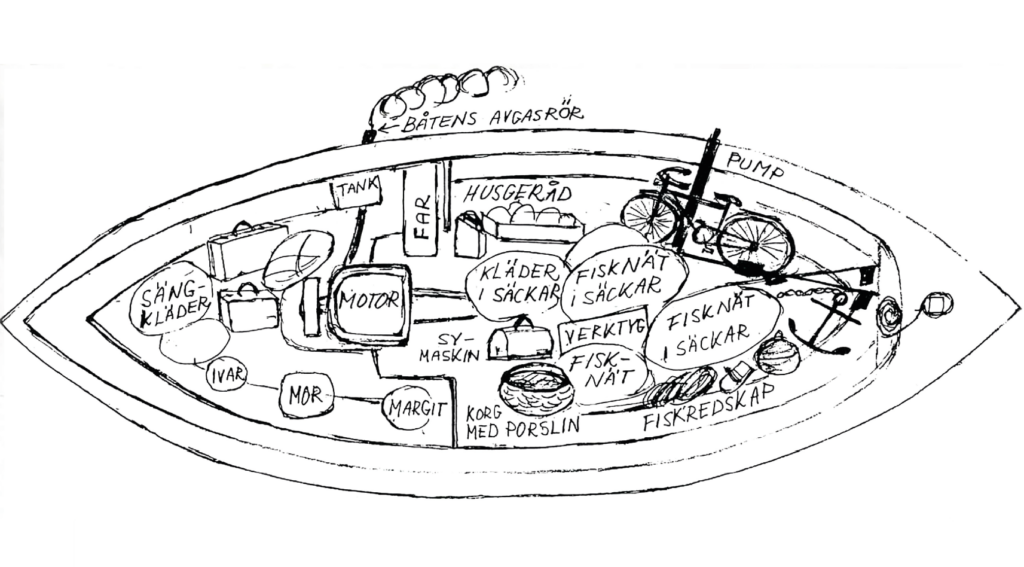

4. novembril 1943 lahkus Viktor Roseni paat Naissaarelt. Paati mahutati ka majakraam, kalavõrgud, rõivad ja isegi jalgratas. Margit Roseni joonistus.

Viktor Rosen’s boat left Naissaar on 4 November 1943. Household effects, fishing nets, clothing, and even a bicycle was fit into the boat. Drawing by Margit Rosen.

Illustratsioon / illustration: erakogu

1944. aasta 4. veebruaril anti Naissaare elanikele korraldus sõjaolukorra tõttu Saksamaale evakueeruda. 6. veebruariks kell 12 pidid elanikud olema saarelt lahkunud. Mitmed noormehed olid saanud mobilisatsiooni käsu. Vallandus suur põgenemine – rasketes oludes läbi talvise mere. Ametlikult oli lubatud lähenevate Nõukogude vägede eest vaid Saksamaale evakueeruda ja salaja üle Soome lahe suunduvad põgenikud riskisid võimalusega saada Saksa mereväelaste poolt tabatud. Mõnel perel õnnestus Rootsi pääseda koos rannarootslastega, kes said kodumaalt lahkuda Rootsi ja Saksamaa vahelise kokkuleppe alusel. Osa naissaarlasi jäi Eestisse.

The order was issued on 4 February 1944 to the residents of Naissaar to evacuate to Germany due to the war situation. The residents were to depart from the island by 12 o’clock on 6 February 1944. Officially, they were only allowed to evacuate to Germany to escape the approaching Soviet forces. Refugees secretly fleeing across the Gulf of Finland risked being caught by German naval seamen. Some families succeeded in escaping to Sweden together with coastal Swedes, who were allowed to leave their homeland on the basis of an agreement between Sweden and Germany. Some Naissaar islanders remained in Estonia.

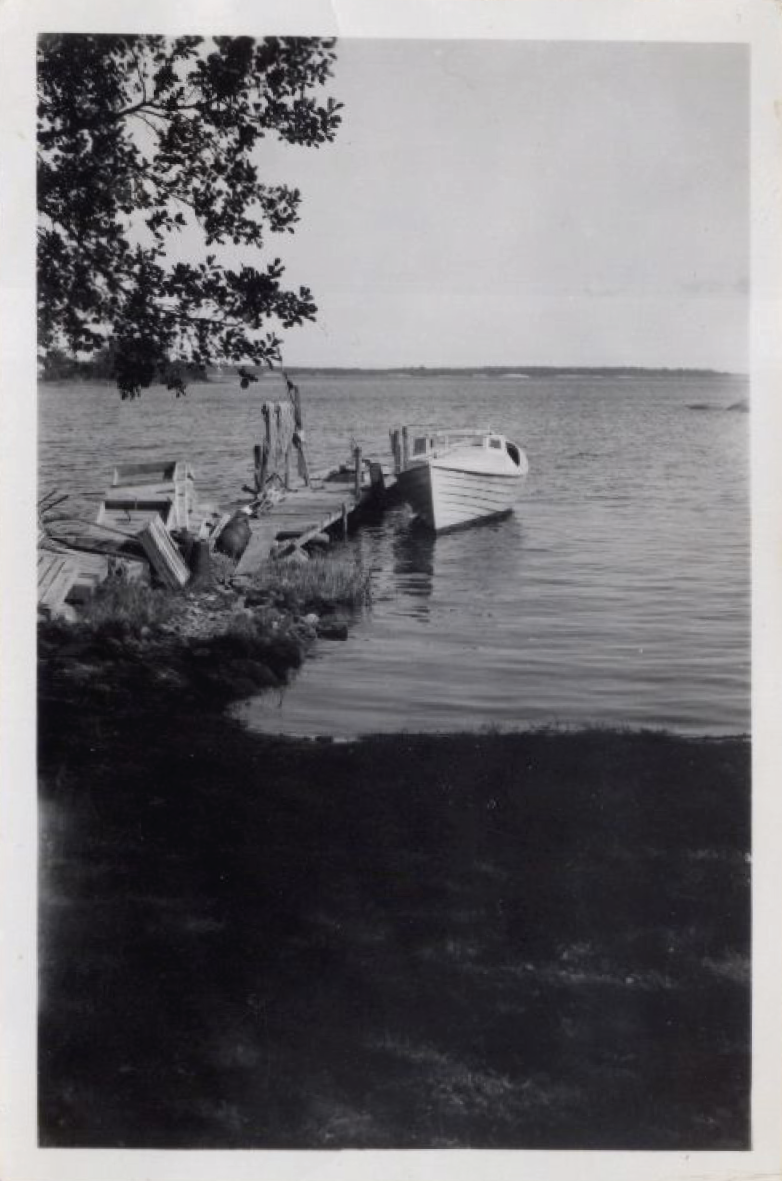

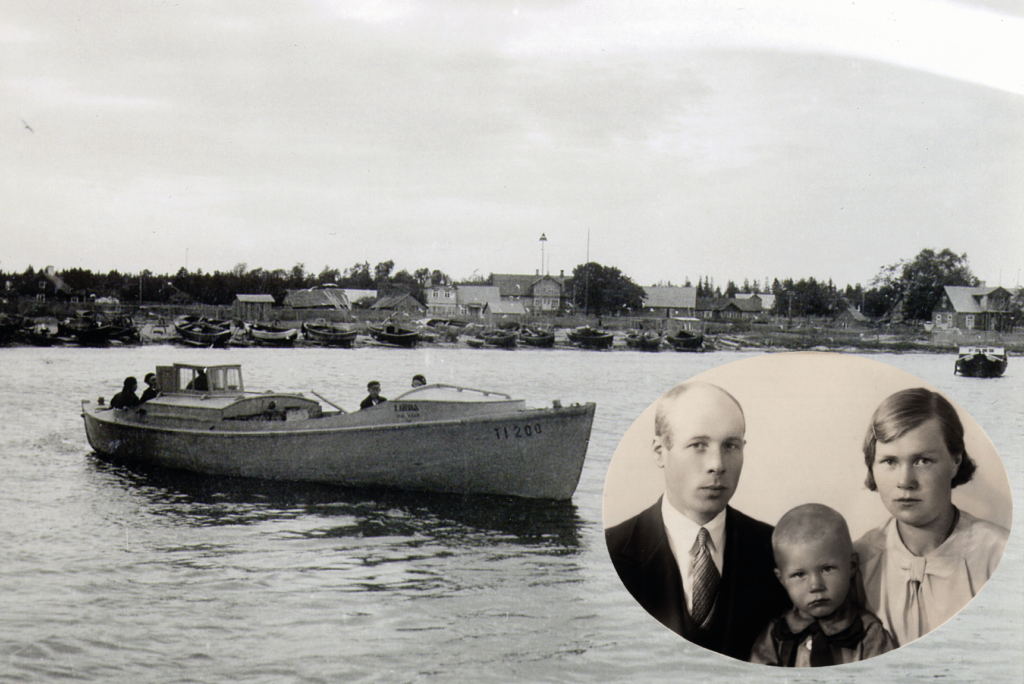

1944. a veebruaris juhtis julge 32-aastane noor naine Elmeri Lillevars paadi üle talvise mere Hankosse, pardal kaks poega ja veel mõned põgenikud. Sõjaeelse meenutusena paat „Linda“ veel Naissaare Lõunaküla all ja Elmeri Rosen Lillevars koos abikaasa ja vanema pojaga. Perepea Edgar Lillevars mobiliseeriti 1941 Punaarmeesse ja jäi kadunuks.

In February of 1944, a courageous 32-year-old young woman named Elmeri Lillevars piloted a boat across the winter sea to Hankö with her two sons and a few other refugees on board. As a prewar recollection, here we see Rosen and Elmeri Lillevars with their eldest son and the boat Linda still at Lõunaküla hamlet on Naissaar. The head of the family Edgar Lillevars was mobilised into the Red Army in 1941 and went missing in action.

Illustratsioon / illustration: erakogu

Ööl vastu 6. veebruari põgenesid Axel Bertelsoni paadiga viimased kaks Põhjaküla peret – 4 täiskasvanut ja 3 last. Kui Nõukogude sõjaväelased sügisel Naissaarele jõudsid, oli saar inimtühi.

On the night before 6 February, the last two families from Põhjaküla hamlet fled in Axel Bertelson’s boat – 4 adults and 3 children. When Soviet soldiers arrived on Naissaar in the autumn, the island was deserted.

PRANGLI JA AKSI

PRANGLI AND AKSI

Saareelanike tulevik oli ebakindel juba enne sõja algust. 14. juunil 1940 olid Prangli kalurid tunnistajaks, kui Nõukogude lennuk tulistas alla Tallinna– Helsingi liinilennuki Kaleva. Teati, et naissaarlased sunniti kodudest lahkuma ja kardeti sama saatuse kordumist. Punaarmee Eestist põgenemisel jõudis 24. augustil 1941 saare idaranda pommitabamuse saanud laev „Eestirand“ mobiliseeritud meestega pardal. Saksa võimud alustasid oma mobilisatsioonidega ning 1943. a põgenes 14 Prangli noormeest selle eest üle mere ja liitus Soome armeega.

Aksi saarel asus piirkonna tähtsaim paadiehituskeskus. Sõja ajal oli Aksi paljudele mandrilt tulnud põgenikele hüppelauaks – saarelt oli kergem põgenemist alustada, ülevedusid korraldati juba 1943. a kevadest. Endel Aksbergi pere kolis Aksilt Soome Pirttisaarele ja sügisel 1943 Trutlandeti saarele. Nende kodu oli põgenike vastuvõtupunkt, Endel tegi kokku 22 põgenikereisi.

The future of the islanders was already uncertain before the start of the war. On 14 June 1940, Prangli fishermen witnessed how a Soviet aircraft shot down the passenger airliner Kaleva, which was flying from Tallinn to Helsinki. They knew that the islanders of Naissaar had been forced to leave their homes and the people of Prangli feared a repeat of that same fate. While the Red Army was fleeing from Estonia, the ship Eestirand with mobilised men on board arrived at the island’s eastern shore on 24 August 1941 after being hit by a bomb. The German authorities started their own mobilisations and in 1943, 14 young men from Prangli fled from the mobilisation across the sea and enlisted in the Finnish Army.

The region’s most important boat-building center was on Aksi Island. During the war, Aksi was a springboard for many refugees from the mainland – it was easier to start the voyage abroad from the island. Trips were already organised starting from the spring of 1943 to ferry refugees across the gulf. Endel Aksberg’s family moved from Aksi to Pirttisaar in Finland and in the autumn of 1943 on to Trutlandet Island. Their home was a station for receiving refugees. Endel made a total of 22 trips to ferry refugees.

Nõukogude vägede lähenedes põgenes Pranglilt ja Aksilt kokku vähemalt 164 inimest – umbes kolmandik saarte toonasest elanikkonnast. Aksi-Madise Aksbergide pere (eestindatult Aaslepp) seadis septembris 1944 ühe mootorpaadi merekõlblikuks. Öö jooksul kogunes saarele üle 30 inimese. Helmut Aksberg kirjutab: „Päikeseloojangu ajaks olime ärasõiduks valmis, kuid papat, isa Aleksandrit, ei olnud kohal. Ta oli oreli juures – mängis viimase loo ja lahkus.“

About a third of the population of those islands at that time – at least 164 people in total – fled from Prangli and Aksi as Soviet forces approached. The Aksberg family (Aaslepp after their name was Estonianised) of Aksi-Madise made a motorboat seaworthy in September of 1944. More than 30 people gathered on the island overnight. ‘We were ready to depart by sunset but papa, the family father Aleksander, was missing. He was at the organ – he played his last piece of music and left.’

Ehitusjärgus paat Aksi-Madise õuel 1942. a suvel. Kajutilael Helmut Aksberg, paadi kõrval Verner karkudega. 1941. a oli Aksilt konfiskeeritud 4 suuremat paati ning vennad Verner ja Helmut hakkasid uut paati ehitama. Töö jäi pooleli, sest vennad vangistati „Soome sõitude“ süüdistusega. Endel Aksberg pukseeris paadi salaja Soome ja tegi korda. Sellest sai põgenikeveo paat.

A boat under construction in the yard of Aksi-Madise in the summer of 1942. Helmut Aksberg is on the cabin ceiling. Verner is on crutches beside the boat. Four large boats had been confiscated from Aksi in 1941 and the brothers Verner and Helmut started building a new boat. The work remained unfinished because the brothers were imprisoned under the accusation of making ‘voyages to Finland’. Endel Aksberg secretly towed the boat to Finland and finished building it. It became a boat for ferrying refugees.

Illustratsioon / illustration: RRM

Kaasa võeti nii palju inimesi kui võimalik, kuid ei mingeid suuri pakke. Tuli valida inimhinged, ja neid maksimaalselt. Paati mahutati umbes kakskümmend inimest või rohkemgi. Ilm oli ilus ja öö varjus sõideti esmalt Soome poole. Hommikuvalguses jõuti Helsingi lähedasele Eestinluoto saarele, seal elasid pere kauged sugulased. Pärast lühikest peatust paadisadamas ja kohtumist Soome rannavalvega, tuli neile appi perekonna noorim poeg Erkki. Ta oli kodumaalt lahkunud juba varem ja osalenud Jätkusõjas. Ta võttis oma mootorpaadi, sõitis ees ja juhatas teed Soome põgenike vastuvõtupunkti Jollases. Seal astusid enamik küüti saanud

kaaspõgenikest maale, abistajatega sõnagi rääkimata, lootuses mugavamalt edasi reisida.

Kuna Soome-Vene vaheline Jätkusõda oli neil päevil lõppenud, siis 19. septembrist kehtiva vaherahu kohaselt pidi Punaarmee lähipäevadel Porkkala ja Hangö aladele sisse marssima. Põgenikud pidid neist paigust enne mööduma. Edasisõit Rootsi suunas arenes läbi Soome saarestiku takistusteta. Ahvenamaa läänepoolsest lootsijaamast lahkuti reede õhtul pimeduse varjus ja hommikuvalguses paistis silmapiiril Rootsi. Seal ootas põgenikke Rootsi päästelaev „Örskär“.

As many people as possible were taken along but no large baggage was brought on board. Human souls had to be prioritised to the maximum. About twenty or more people were fit into the boat. The weather was fine, and the boat went first toward Finland under cover of night. In the morning light, they reached Eestinluoto Island near Helsinki. That is where the family’s distant relatives lived. After a brief stop at the boat harbour and an encounter with Finnish border guards, the family’s youngest son Erkki came to their assistance. He had already left his homeland earlier and had participated in Finland’s Continuation War. He took the lead in his own motorboat and guided them to a Finnish refugee reception station in Jollase. There most of their fellow refugees who had been brought across the sea stepped ashore without saying a word to those who had helped them, hoping to continue their journey in more comfortable conditions.

Since the Continuation War between Finland and Russia had ended in those days, according to the armistice that went into effect on 19 September, the Red Army was to march into the regions of Porkkala and Hankö in the next few days. The refugees had to get past those areas before that happened. Their voyage onward in the direction of Sweden continued through the Finnish archipelago without hindrances. They departed from Åland’s western pilot station on Friday evening under cover of darkness and Sweden appeared on the horizon in the morning light. There the Swedish rescue ship Örskär awaited the refugees.

Aksbergi vennad 1947. a metsas paati ehitamas. Paat tehti suur – et sinna mahuks kogu perekond, kui oleks vaja olnud edasi Kanadasse põgeneda. Perekond aga jäi Rootsi paigale.

The Aksberg brothers building a boat in the woods in 1947. The boat was large – so that the entire family could fit on board in case it would become necessary to flee onward to

Canada. However, the family remained in Sweden.

Illustratsioon / illustration: RRM

TARTU

Koostaja/Compiled by: Martin Jaigma

Augusti keskpaigas 1944 jõudis sõjaärevus, mida toitsid kulutulena levivad kuulujutud, taas Tartusse. Paljudel juhtudel tähendas see vähem või rohkem keerulist pagemisteed põhja- või läänerannikule. Ühtset skeemi ei olnud – kas põgeneti, oldi mobiliseeritud töö- või väeteenistusse, evakueeritud või rännati välja mingil muul põhjusel. Tartus toonaste sündmuste tunnistaja literaat Jaan Roos kirjeldab, kuidas kord registreeriti lapsi ja naisi sõiduks läbi Paldiski Soome, mis osutus tühjaks lubaduseks, kord kõlas käsk evakueerida linna Emajõe lõunapoolne külg, kord kahe tunni jooksul kogu linn, kusjuures käsu eirajad lubati maha lasta, samuti õhku lasta linna suurimad hooned. Samal ajal manitses Nõukogude propagandaraadio inimesi linnast mitte lahkuma …

War anxiety fed by rumours that spread like wildfire reached Tartu again in mid-August of 1944. In many cases, that meant a more or less difficult exodus route to the northern or western coast. There was no single approach – people fled, were mobilised into labour service or military service, were evacuated, or emigrated for some other reason. The man of letters Jaan Roos witnessed the events of that time in Tartu. He describes how children and women were once registered to be taken via Paldiski to Finland, which proved to be an empty promise. On another occasion, the order was issued to evacuate the side of the city on the southern bank of the Emajõgi River, while another order stated that the entire city had to be evacuated within two hours, whereas people who disobeyed the order were to be shot, and the city’s largest buildings were to be blown up. At the same time, Soviet propaganda radio urged people not to leave the city…

Punaarmee vallutas Tartu 25. augustil 1944. Selleks ajaks oli linnaelanikkond suures osas juba evakueerunud. Lahkunud olid linnavõimu ametkonnad, aga ka muud Tartu sümbolid, näiteks ajaleht „Postimees“, mille 25. augusti number andis teada, et „Bolševistliku vaenlase roimarlik katse vallutada meie väikest Eestit on sundinud ka „Postimeest“ ajutiselt siirduma põlisest asukohast Tartu linnast Viljandi linna.“ Ülikooli rektoraat lahkus Tartust 24. augustil, ametlikult lõpetas Tallinnasse suundunud rektor Edgar Kant ülikooli tegevuse 18. septembril.

The Red Army captured Tartu on 25 August 1944. By that time, city residents had largely already been evacuated. The agencies of the municipal authorities had also left along with other symbols of Tartu, such as the Postimees newspaper. Its edition of 25 August announced that ‘the bolshevist enemy’s criminal attempt to capture our little Estonia has forced the Postimees to also move temporarily from its native location in the city of Tartu to the city of Viljandi’. The rector’s office of the university left Tartu on 24 August. Rector Edgar Kant went to Tallinn and officially terminated the activity of the university on 18 September.

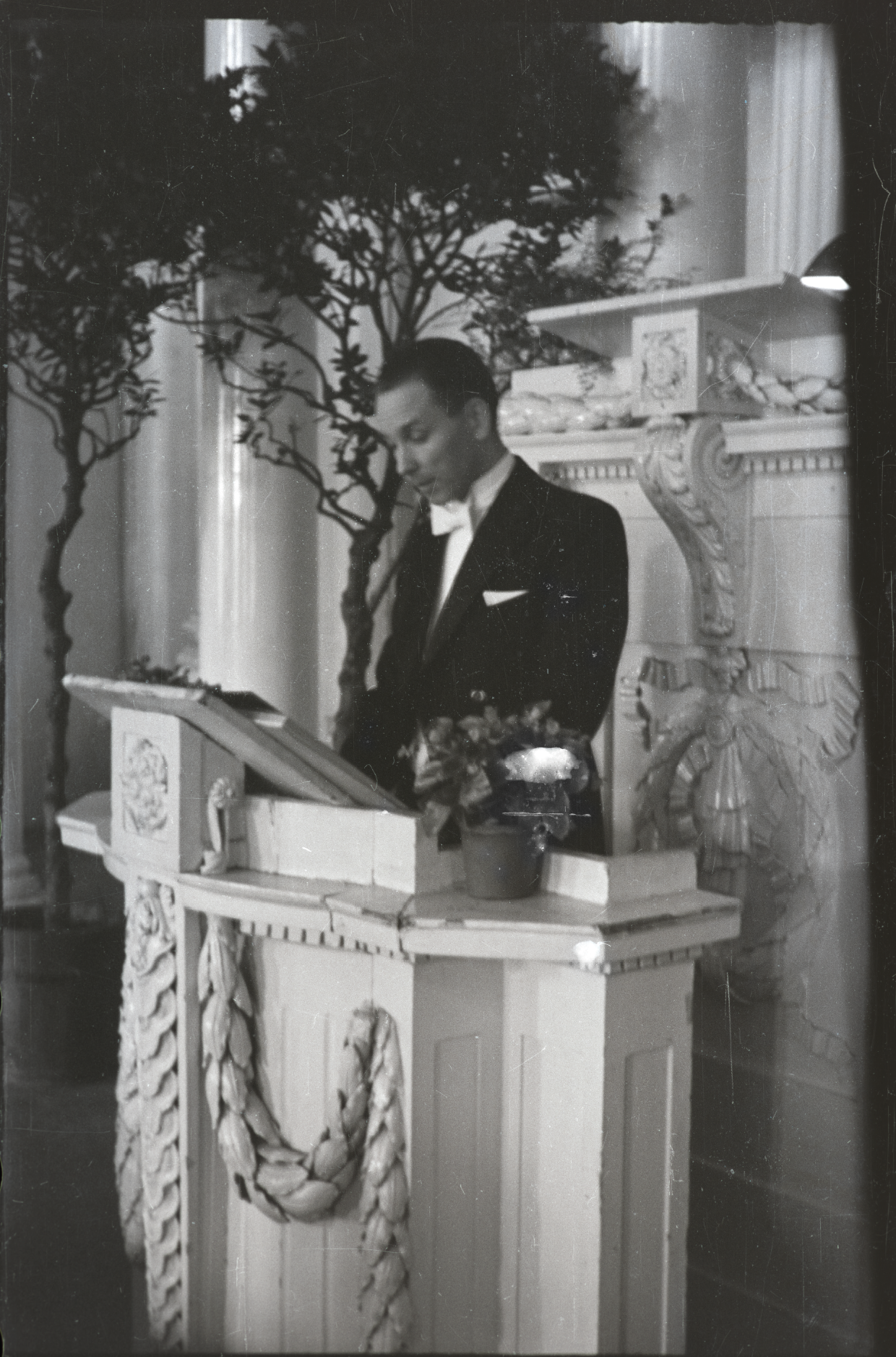

Teatri Vanemuine orkestri dirigent Eduard Tubin (paremal) katmas teatri fassaadi õhurünnakute kartuses kamuflaaž värviga mais 1944.

Eduard Tubin (on the right), conductor of the Vanemuine Theatre Orchestra, covering the theatre facade with camouflage paint in fear of air raids in May 1944.

Illustratsioon / illustration: RA

1941. a sõjasuvi oli Tartu ülikooli suhteliselt kergelt riivanud, enamik ülikooli hallatavast 172 hoonest oli alles. Isegi peahoone oli imetabasel kombel mürsutabamustest puutumata, ehkki kaks nädalat rindelinnaks olemist oli suure osa linnasüdamikust varemeteks muutnud. Ülikooli õppetöö oli seoses üldmobilisatsiooniga katkenud juba 1944. a märtsis ning sama kuu lõpus langes linn Punaarmee massiivse õhurünnaku ohvriks. See andis paljudele tõuke linnast lahkuda ning otsida pidepunkti mujal Eestis. Juba kevadel oli alanud ka Tartu ülikooli varade ning töötajate päästmine, mille eestvedajaks sai kunstiajaloo professor Armin Tuulse, hiljem etnograaf Gustav Ränk.

The war in the summer of 1941 had affected the University of Tartu relatively little. Most of the 172 buildings administered by the university survived. Even its main building was miraculously spared from artillery strikes regardless of the fact that two weeks as a front-line city had reduced a sizable part of the city centre to ruins. Teaching had already ceased at the university in connection with the general mobilisation in March of 1944. The city suffered a massive Red Army bombing raid at the end of that same month. That provided the impetus for many to leave the city and seek shelter elsewhere in Estonia. The rescue of the property and employees of the University of Tartu had also already begun in the spring. Professor of Art History Armin Tuulse led those efforts, followed later by the ethnographer Gustav Ränk.

Õnneks läks eestlastest ametnikel korda väärata Saksa võimude plaan viia ülikool üle Warthegausse (tänasel Poola alal, keskusega Poznanis) ning hiljem Königsbergi. Ülikooli varad ja inimesed hajutati üle Eesti: Haapsalu–Uuemõisa, Viljandi- ja Põhja-Tartumaale, Tallinnasse. Selle käigus lahkus Tartust umbes 400 ülikooliga seotud inimest. Septembris, teise Nõukogude okupatsiooni alguses, oli Tartus väidetavalt kohal ainult üks õppejõud – õigusteaduste professor Elmar Ilus. Alles oktoobris, kui Haapsalust naasis 281 arstiteaduskonna töötajat, kes polnud Eestist lahkunud, sai mõelda ülikooli avamise peale. Ülikooli töö taastati 24. oktoobril 1944.

Fortunately, Estonian officials succeeded in averting the plans of the German authorities to transfer the university to Warthegau (in present-day Polish territory with its centre in Poznan) and later to Königsberg. University property and its employees were spread throughout Estonia: to Haapsalu- Uuemõisa, Viljandi and Northern Tartu counties, and Tallinn. Together with the university, around 400 people associated with the university left Tartu. One lecturer – the law professor Elmar Ilus – was reportedly the only one who remained in Tartu in September at the start of the second Soviet occupation. It was not until October, when 281 employees from the Faculty of Medicine, who had not left Estonia, returned from Haapsalu, that the opening of the university could even be considered. The university began operating once again on 24 October 1944.

Tartu ülikooli rahvaluule arhiivi (tänase Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi) evakueeritud varade vedu Palivere jaamast Liivi algkooli, 1944.

Transportation of property that had been evacuated from the University of Tartu folklore archive (currently at the Estonian Literary Museum) from Palivere station to Liivi elementary school, 1944.

Illustratsioon / illustration: KIRMUS

PÕGENEMINE

FLIGHT

1944. a sügisel põgeneti nii Rootsi kui Saksamaale, kuid Tartu intelligents võttis eelissuuna Rootsi poole. Seda toetasid sealsed eestlaste juhitud abiorganisatsioonid, mille eesmärgiks oli päästa Eesti haritlaskond. Samas oli Tartust pärit inimeste osakaal märkimisväärne ka Saksamaal asuvates pagulaslaagrites, näiteks Geislingenis.

People fled to both Sweden and Germany in the autumn of 1944, yet the preferred destination of Tartu’s intellectuals was Sweden. Sweden’s aid organisations run by Estonians supported that development. Its aim was to save Estonia’s intellectuals. At the same time, the relative proportion of people from Tartu at the numerous refugee camps in Germany was also considerable, for instance in Geislingen.

Professor Armin Tuulse oli juba 1930. aastail oma teadustöö raames Rootsis tegutsenud ning nüüd kostis tema ning teiste haritlaste eest Rootsi riigiarhivaar Sigurd Curman. Tänu sellele õnnestus mitmetel haritlastel suunduda Rootsi mootorpurjekal „Juhan“, mis oli Saksa võimudelt saanud loa rannarootslaste evakueerimiseks. Lisaks professor Tuulse perekonnale jõudis sama laevaga Rootsi näiteks professor Aadu Lüüs, kes oli olnud Tartu ülikooli arstiteaduskonna dekaan. Septembris jõudsid Rootsi ka helilooja Eduard Tubin ning Tartu ülikooli rektor Edgar Kant, kes lahkus koos presidendi kohusetäitja Jüri Uluotsaga.

Professor Armin Tuulse had already worked in Sweden within the framework of his research work in the 1930s. Now Sweden’s National Archivist Sigurd Curman vouched for him and other intellectuals. For that reason, several intellectuals succeeded in going to Sweden on board the motor sailboat Juhan, which had received permission from the German authorities to evacuate the coastal Swedes. In addition to the family of Professor Tuulse, Professor Aadu Lüüs, who had served as dean of the University of Tartu Faculty of Medicine, arrived in Sweden on board the same ship. The composer Eduard Tubin and the Rector of the University of Tartu Edgar Kant, who left together with Jüri Uluots, the Prime Minister of Estonia in the duties of President, also reached Sweden in September.

Oli ka neid, kellel ei läinud kõik plaanikohaselt. Plaan laevaga Rootsi põgeneda luhtus näiteks kirjanik Friedebert Tuglasel ja tema abikaasal Elo Tuglasel. Suvel 1944 pagesid nad läheneva Punaarmee eest esmalt Viljandimaale ja sealt Tallinnasse, kus peatuti Marie Underi ning Artur Adsoni juures. Under ja Adson pääsesid Tallinnast veel mootorpurjekas „Triina“ pardale 20. septembril, mis oli viimane Saksa võimudega kooskõlastatud reis rannarootslaste evakueerimiseks. Tuglased sinna peale aga ei mahtunud ning paar lahkus Tallinnast, proovides õnne läänerannikul, aga sedagi ei krooninud edu. Lõpuks suunduti jalgsi tagasi Viljandi poole, Nõukogude võimu haardest enam ei pääsetud.

There were also those for whom everything did not go according to plans. For instance, the plan of the writer Fridebert Tuglas and his wife Elo Tuglas to flee by ship to Sweden came to nought. They fled to Viljandi County ahead of the advancing Red Army in the summer of 1944 and from there to Tallinn, where they stayed with Marie Under and Artur Adson. Under and Adson made it on board the motor sailboat Triina, which left Tallinn on 20 September and was the last voyage for evacuating coastal Swedes that had been agreed to with the German authorities. There was no space on board for the Tuglases and the couple left Tallinn, trying their luck on the west coast, but that did not succeed either. Finally, they went back towards Viljandi on foot. They could no longer escape the grasp of the Soviet regime.

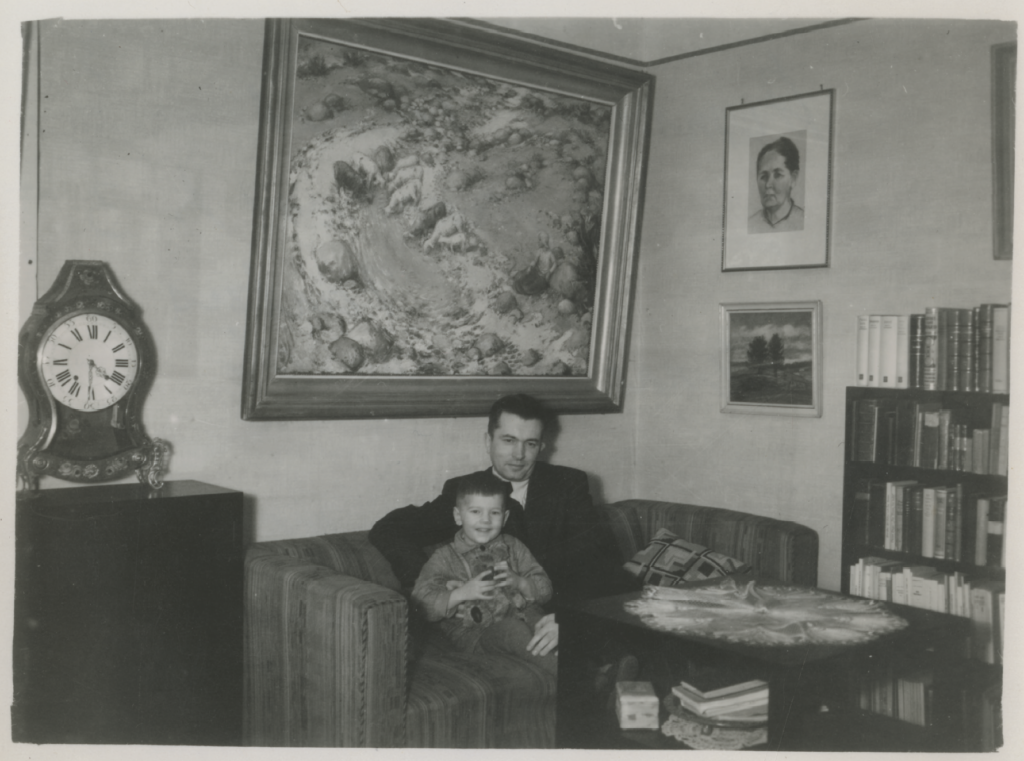

Tehti aga ka teistsuguseid otsuseid. Pärast sõja lõppu 1945. a pöördus Tartusse tagasi mobiliseerituna Saksamaale sattunud füüsik ja tulevane Teaduste Akadeemia liige Harald Keres, hilisem Tartu linna aukodanik ning maletaja Paul Kerese vend. Nende pere kaotas Tartus märtsipommitamistes oma kodu ning Haraldi tütar oli koos vanaemaga juba varem sõja eest Pärnumaale saadetud. Augustis asus Harald koos naisega jalgratastega ka ise teele, alguses Haapsallu, siis Tallinnasse. Tallinnas võeti Harald Saksa võimude poolt mereväe abiteenistuslaste hooldusõpetajaks ning evakueeriti üksuse koosseisus transpordilaevaga Saksamaale. Pärast sõja lõppu otsustas Harald Keres mitte läände suunduda, vaid hoopis Eestisse tagasi seigelda, mis tal ka õnnestus.

Other kinds of decisions were also made. After the end of the war in 1945, the physicist and future member of the Academy of Sciences Harald Keres, who had been mobilised and taken to Germany, returned to Tartu. Harald was the brother of the chess master Paul Keres and was later made an honorary citizen of the city of Tartu. Their family had lost their home in Tartu when the city was bombed in March of 1944. Harald’s daughter had already been sent to Pärnu County with her grandmother earlier to keep them out of harm’s way. In August, Harald left Tartu together with his wife by bicycle, first to Haapsalu and then to Tallinn. In Tallinn, the German authorities hired Harald as pastoral support teacher for men in the navy auxiliary service. He was evacuated in the ranks of that unit on a transport ship to Germany. After the end of the war, Harald Keres decided not to go to the West, but rather to return to Estonia. He succeeded in that adventure.

Täpseid arve ja usaldusväärset statistikat, kuhu ja kui palju Tartu kandi inimesi 1944. a sügisel Eestist välja liikus, praegu pole. 1941. a oli Tartu elanike arv 59 500, 1945. a üksnes 34 000. Sõda oli oluliselt muutnud nii linna välist ilmet kui ka demograafi list pilti.

There currently are no exact figures and reliable statistics on how many people from the Tartu area left Estonia in the autumn of 1944 and where they went. The population of Tartu was 59,500 in 1941, but only 34,000 in 1945. The war had significantly altered the city’s external appearance as well as its demographic structure.

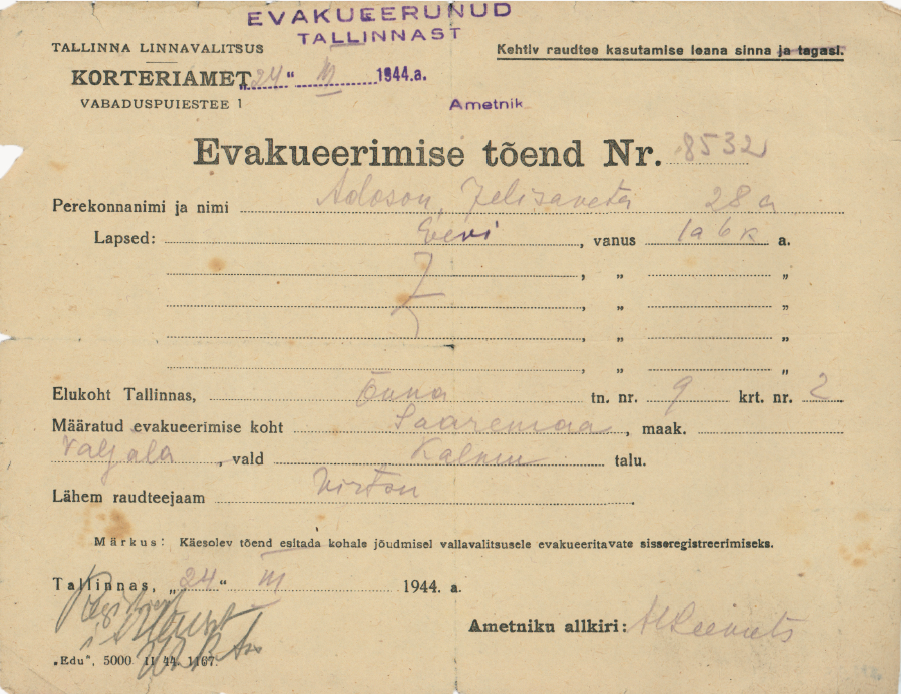

LAHKUMINE TALLINNAST

FLIGHT FROM TALLINN

Koostaja/Compiled by: Meelis Maripuu, Ülle Kraft, Aivar Niglas

1944. aasta aprillis, kui Punaarmee surus Eesti piiridele, oli Saksa väejuhatus otsustanud Tallinna välja ehitada „kindlustatud linnaks“ (Fester Platz), mis pidanuks pikemat aega vastu pidama vastase rünnakutele. Soome vaherahu NSV Liiduga 4. septembril ning väljumine sõjast jättis siinse rinde põhjatiiva kaitseta ning muutis sõjalist olukorda drastiliselt. Kuigi Hitler oli andnud käsu rinnet iga hinna eest hoida, alustas maavägede juhtkond kiireid ettevalmistusi Eestist taandumiseks. 14. septembril alustas Punaarmee siinses piirkonnas ulatuslikku pealetungi.

In April of 1944, when the Red Army approached Estonia’s borders, German Army Command had decided to turn Tallinn into a ‘fortified city’ (Fester Platz), which was meant to withstand enemy attacks at length. Finland’s ceasefire with the Soviet Union on 4 September and its exit from the war left the northern flank of the front in Estonia defenceless and drastically altered the military situation. Although Hitler had issued an order to hold the front at all costs, German Ground Forces Command started rapid preparations for retreating from Estonia. On 14 September, the Red Army launched an extensive offensive in the region around Estonia.

16. septembril andis Hitler siiski nõusoleku evakueerimisplaani „Aster“ käivitamiseks, kuna vastasel korral ähvardas kogu väegruppi Nord kotti jäämine. Algse kava kohaselt pidi Tallinna evakueerimiseks kuluma 12 päeva, kuid Punaarmee üha tugevneva surve all viidi see läbi kuue päevaga. 28. septembriks oli juba kogu Mandri-Eesti langenud Nõukogude okupatsiooni alla.

On 16 September, Hitler nevertheless granted his consent for implementing the Aster evacuation plan since otherwise the entire Nord Army Group was in danger of being encircled. The initial plan estimated that it would take 12 days to evacuate Tallinn, yet under ever increasing Red Army pressure, it was completed in six days. By 28 September, the Soviets already occupied all of continental Estonia.

17. septembril algas Punaarmee rünnak Emajõe rindel ja see murti läbi. Tallinna evakueerimist pidi ca 10 000 mehega katma kindral Gerocki lahingugrupp, kellele allutati ka Tallinna komandandi, kindralmajori Artur Bisle ja Paldiski komandandi lahingugrupid. Evakuatsiooni korraldamise põhiraskus langes Idapoolse Läänemere Admiralile, (Kommandierender Admiral östliche Ostsee) viitseadmiral Theodor Burchardile. Tema käsutuses oli selleks umbes 50 erinevat ujuvvahendit, kuid neid tuli alles hakata Tallinna koondama ja suurem hulk laevu jõudis Tallinnasse alles 19. septembril. Saksa evakueerimiskomissari hinnangu kohaselt oli lisaks sõjaväelastele vaja evakueerida 35 000 isikut.

On 17 September, the Red Army offensive along the Emajõgi Front began and achieved a breakthrough. General Gerock’s battle group of about 10,000 men was assigned to cover the evacuation of Tallinn. The battle groups of the commandants of Tallinn, Major General Artur Bisle, and Paldiski were additionally placed under Gerock’s command. Vice Admiral Theodor Burchard, the Kommandierender Admiral östliche Ostsee (Commanding Admiral of the eastern Baltic Sea), was assigned the main responsibility for organising the evacuation. He had about 50 various floating vessels at his disposal for this purpose, but they were not at Tallinn yet. He had to start having them sent to Tallinn. Most of the ships did not reach Tallinn until 19 September. According to the estimation of the German evacuation commissar, 35,000 persons had to be evacuated in addition to military personnel.

18. septembril tunnistati lõplikult hädavajadust alustada kiireimas korras üksuste evakueerimist ning esimesed 3000 meest saadeti teele. Sadamas avanenud pilt rääkis selget keelt sellest, et lahkujad üritasid kaasa viia suurt hulka keelatud sõjasaaki. Kaose vältimiseks otsustati karmilt toimuvasse sekkuda ning järgmisel päeval suudeti sadamas tagada rahuldav kord.

The urgent need to start evacuating military units as quickly as possible was finally recognised on 18 September and the first 3,000 men were sent on their way. The scene at the harbour clearly indicated that the departees were trying to take along with them a large quantity of forbidden war booty. To prevent chaos, it was decided to harshly intervene in that, which was taking place there. Satisfactory order was successfully restored at the harbour on the next day.

Admiral Pitka püüdis organiseerida Eesti üksuste vastupanu Punaarmeele ja soovitas inimestel kodumaalt mitte põgeneda. Pitka üleskutsega lendlehtede jagamine 21. septembril 1944.

Admiral Pitka tried to organise resistance to the Red Army by Estonian units and urged people not to flee from their homeland. Distribution of flyers bearing Pitka’s appeal, 21 September 1944.

Illustratsioon / illustration: RA

Arvestades vähest laevade hulka, otsustati evakueerimist vajavad vangid paigutada mitte laevadele, vaid saata jalgsimarsil Saaremaale, kust nad hiljem meritsi evakueeriti. Klooga koonduslaagris olnud juutide osas langetas SS paraku teistsuguse otsuse, seni kavas olnud evakueerimise asemel nad hukati. Tallinna keskvanglasse oli jäänud veel üle 1500 vangi, kes saadeti samuti jalgsimarsil lääneranniku suunas, kuid esmalt valvemeeskond ja seejärel ka vangid hajusid enne sihtkohta jõudmist.

Considering the small quantity of ships available, it was decided not to place prisoners in need of evacuation on ships, but rather to send them on foot to Saaremaa, from where they were later evacuated by sea. Sadly, the SS made a different decision regarding Jews at the Klooga concentration camp. They were executed instead of the evacuation that had been planned until then. More than 1,500 prisoners still remained in Tallinn’s central prison. They were similarly sent to march on foot towards the western coast, but first the convoy guards and thereafter the prisoners themselves dispersed before reaching their destination.

18. septembri õhtul andis Vabariigi Presidendi ülesandeid täitev Jüri Uluots Otto Tiefi le üle valitsuse moodustamise käskkirja: „Sakslased taganevad Eestist. Aeg on tegutseda! Koguge kokku valitsuse liikmed ning asuge tegevusse.“

On the evening of 18 September, Jüri Uluots, acting in the duties of the President of the Republic of Estonia, handed Otto Tief the directive to form the government of the Republic of Estonia: ‘The Germans are retreating from Estonia. Now is the time to act! Gather the members of the government together and take action.’ Unfortunately, the formation of the Estonian government remained a symbolic act at that moment.

Illustratsioon / illustration: TLM

EVAKUEERIMISE KÄIK

EVACUATION PROCESS

19. septembril paigutati laevadele umbes 8000 inimest. Esmajoones oli tegu Virumaalt evakueeritud BaltÖli tööliste ja personaliga ning Saksa sõjaväelastega. Päeva jooksul hakkasid Tallinna saabuma tühjad laevad, mis laaditi täis järgmisel päeval. Evakueerimise tegi veelgi keerukamaks asjaolu, et mereväe alluvusse antud eesti lenduritest moodustatud lennuüksus (Aufklärungsfl iegegruppe 127) lõpetas oma luurelennud ning evakueerimise korraldajatel puudus ülevaade olukorrast rindel.

20. september kujunes evakuatsiooni keskseks päevaks. Tingimused olid soodsad: saabunud oli piisavalt laevu, meri oli praktiliselt tuulevaikne, Nõukogude lennuväe tegevus pea olematu. Viiel suurel aurikul ning väiksematel abilaevadel lahkus sel päeval Tallinnast eri andmetel 21 000 – 23 000 inimest, nende hulgas laeval „Wartheland“ Saksa tsiviilametnikud ja Saksa võimude teenistuses olnud eestlased oma pere liikmetega. Päeva lõpuks suudeti enamik sadamasse saabunuid paigutada laevadele.

About 8,000 people were loaded onto ships on 19 September. Most of them were German military personnel along with workers and personnel from the BaltÖl mines and factories who had been evacuated from Viru County. Empty ships started arriving at Tallinn over the course of the day. They were loaded up on the following day. The fact that the Aufklärungsfliegegruppe 127 air force unit formed out of Estonian pilots, which had been placed under the command of the navy, had discontinued its reconnaissance flights made the evacuation even more complicated since the organisers of the evacuation had no overview of the situation at the front.

20 September turned out to be the primary day of the evacuation. The conditions were favourable: a sufficient number of ships had arrived, the sea was practically calm, and the Soviet air force was almost inactive. According to various sources, 21,000–23,000 people left Tallinn on that day on board five large steamships and smaller auxiliary ships. Among them, the ship Wartheland transported German civilian public servants and Estonians who had worked in the service of the German authorities, along with their family members. Most of the people who had come to the harbour were successfully loaded onto ships by the end of the day.

Eestimaa kindralkomissar Karl-Siegmund Litzmann (esiplaanil) lahkub Eestist koos teiste Saksa võimuesindajatega laeval „Wartheland“ 20. septembril 1944.

Karl-Siegmund Litzmann, the Commissar General of Estland (in the foreground), leaves Estonia on the ship Wartheland together with other representatives of the German authorities, 20 September 1944.

Illustratsioon / illustration: ERM

Raskelt haige riigipea kt Jüri Uluots lahkus 20. septembri hommikul Rootsi, et säilitada paguluses Eesti riiklikku järjepidevust. Otto Tiefi valitsus oli selleks ajaks juba kaks päeva ametis olnud, kuid kohalikud Saksa võimukandjad ei paistnud end sellest häirida laskvat.

Tõsisem ja kõigile nähtav märk oli sinimustvalge lipp, mis 20. septembril pärast kindralkomissari ametkonna lahkumist Pika Hermanni torni tõmmati. Rahvas rõõmustas ning lasi sakslaste hinnangul end eksitada valedest lootustest ning alusetutest kuulujuttudest, mille tulemusena vähenes sakslaste hinnangul järgmisel päeval märgatavalt evakueeruda soovivate eestlaste hulk

Estonia’s head of state Jüri Uluots, who was seriously ill, left for Sweden on the morning of 20 September to preserve the continuity of Estonia’s independent statehood in exile. By then, Otto Tief’s government had already been in office for two days but the representatives of the local German authorities did not appear to let that disturb them.

The blue, black, and white flag was a more tangible sign that was visible to all when it was hoisted at the tip of Pikk Hermann Tower on 20 September after the Commissar General’s office had left. The people rejoiced. In the estimation of the Germans, Estonians allowed themselves to be misled by false hopes and groundless rumours, as a result of which, in the estimation of the Germans, the number of Estonians wishing to evacuate dropped considerably on the following day.

21. septembril oli selge, et Saksa maavägedel õnnestub taanduda maad mööda lõuna suunas ning seega vähenes oluliselt evakueerimist vajavate

sõjaväelaste arv. 21. ja 22. septembril paigutati laevadele veel ligikaudu 10 000 tsiviilisikut ning teist samapalju sõjaväelasi, kes olid moodustanud linna viimase kaitse. Öösel toimusid sadamas relvastatud kokkupõrked eestlaste ja sakslaste vahel. Saksa andmeil tapeti umbes 25 eestlast ning 150 relvitustatud eesti sõjaväelast saadeti tööjõuna Saksamaale.

22. septembri hommikul kell 10 olid viimased evakueerumist kaitsnud üksused laevadel ning viimaseid Tallinna reidilt lahkuvaid laevu saatis teele Pirita poolt tulistatud mürsk, mis arvati pärinevat esimestelt kohale jõudnud Punaarmee tankidelt. Pool tundi hiljem sisenes Tartu maanteed pidi linna Punaarmee Eesti laskurkorpuse propagandistlik eelsalk, kellel ei õnnestunud lahkuvatele sakslastele ilmselt ka mitte sümboolset püssipauku järgi lasta.

On 21 September, it was clear that German ground troops would be able to retreat by land towards the south. Thus, the number of military personnel that had to be evacuated markedly decreased. On 21 and 22 September, another roughly 10,000 civilians and the same number of military personnel, who had manned the city’s last line of defence, were loaded onto ships. Armed skirmishes broke out between Estonians and Germans at night at the harbour. According to information from German sources, around 25 Estonians were killed, and 150 armed Estonian soldiers were sent to Germany as labour manpower.

At 10 o’clock on the morning of 22 September, the last units that had covered the evacuation were on board ships. A shell fired from the direction of Pirita, which was thought to be from the first Red Army tanks that had arrived, sent off the ships departing from Tallinn’s roads. A half hour later,’ the propagandistic advance party of the Red Army Estonian Rifle Corps entered the city along Tartu Highway. It evidently was not able to fire even a symbolic rifle shot after the departing Germans.

Kokkuvõttes oli 17.–22. septembrini Tallinnast Saksa võimude organiseerimisel evakueeritud vähemalt 50 000 inimest, sh üle 27 000 tsiviilisiku, kellest valdava osa moodustasid eestlased. Tallinlaste kõrval oli suurem osa laevadele asunud eestlasi saabunud teistest maakondadest otsima võimalust punaterrori eest pääseda.

Transpordilaevad „Malgache“, „Sumatra“ ja „Gotenland“ lahkusid Tallinnast tühjalt, sest nende jaoks ei jätkunud evakueeritavaid, hinnanguliselt suudetuks evakueerida veel vähemalt 2000–2500 isikut.

In sum, at least 50,000 people, including over 27,000 civilians, of whom the vast majority were Estonians, were evacuated from Tallinn as organised by the German authorities from 17 to 22 September. Alongside Tallinners, the greater part of the Estonians who boarded the ships had come from other counties seeking the chance to escape from the Red Terror.

The transport ships Malgache, Sumatra, and Gotenland departed from Tallinn empty because there were no more people seeking to be evacuated to load onto those ships. At least another estimated 2,000 to 2,500 people could have been evacuated.

Enamik Tallinnast teele asunud laevu jõudis kaotusteta sihtpunkti. Suurim tragöödia tabas 21. septembril lahkunud laatsaretlaeva „Moero“, mis Nõukogude lennukite rünnaku tulemusena 22. septembri hommikupoolikul Ventspilsi lähedal uppus. Nii hukkunute kui ka pääsenute arvu osas puudub kindel teadmine. Saksa mereväe andmeil asus Tallinnas laeva pardale üle 1200 inimese, neist pooled haavatud sõdurid, kel polnud mingit pääsemislootust. Hukkus ka sadu Eesti põgenikke, enam kui sajal õnnestus siiski pääseda.

Most of the ships that departed from Tallinn reached their destinations without losses. The greatest tragedy struck the hospital ship Moero, which departed on 21 September and sank near Ventspils on the morning of 22 September as the result of an attack by Soviet warplanes. It is not known for certain how many people perished and how many people were rescued. According to the German Navy, more than 1,200 people boarded

the ship in Tallinn. Half of them were wounded soldiers who had no hope of being rescued. Hundreds of Estonian refugees also perished, yet more than a hundred Estonians managed to survive.

1996. aastal püstitati „Moerol“ hukkunutele mälestusrist lähimale Eesti kalmistule Sõrve poolsaarel Jämaja kalmistul.

In 1996, a cross in memory of the people who perished on board the Moero was erected in Jämaja Cemetery on Sõrve Peninsula, the Estonian cemetery that is closest to the spot where the ship sank.

Illustratsioon / illustration: EVM

PÕGENEMINE HIIUMAALT

EXODUS FROM HIIUMAA

Koostaja/Compiled by: Patrick Rang, Mart Mõniste, Enn Veevo.

Sarnaselt teistele Eesti piirkondadele algas Hiiumaalt põgenemine 1943. aastal: Saksa mobilisatsiooni eest kõrvale hoidmise, Soome armeega liitumise ja vähemal määral eestirootslaste põgenemise käigus. Verepuhtaid rootslasi oli selleks ajaks Hiiumaale jäänud napilt, küll aga leiti arvukalt hiiurootsi esivanemaid, kelle olemasolu tõendamine andis lootust saada luba Eestist lahkumiseks.

Similarly to other Estonian areas, people started fleeing from Hiiumaa in 1943: to evade German mobilisation, to join the Finnish Army, and to a lesser extent the exodus of Estonian Swedes. By that time, few pureblooded Swedes remained in Hiiumaa, yet many islanders discovered that they had Swedish ancestors from Hiiumaa. Proving their existence provided hope for obtaining permits to leave Estonia.

Saksa võimud üritasid pea viimse hetkeni põgenemisi takistada. Nii jäi ära ka tänaseks legendi seisu tõusnud hiidlaste mootorpurjeka „Alar“ põgenemine. Kapten Feliks Voolens otsustas koos meeskonna, pere ja kaasa võetud põgenikega Kõrgessaarest teele asuda 9. septembril 1944, kuid Saksa valvekaater katkestas teekonna. Kinnivõetutega siiski suuremat kurja ei sündinud ja nii mõnigi laeval olnu pääses veel samal sügisel põgenema. Sakslased viisid „Alari“ evakueerudes Saksamaale, kuid pärast sõda õnnestus läände jõudnud omanikel laev tagasi saada ning see on tänaseni säilinud. 1998. aastast on ta tagasi kodusaarel, Sõru sadamas.

The German authorities tried to prevent people from fleeing until almost the last minute. Thus, the escape of the motor sailboat Alar, which belonged to Hiiumaa islanders and has become a legend, did not materialise. Captain Feliks Voolens decided to set sail from Kõrgessaare on 9 September 1944 together with his crew, family, and refugees whom he had taken along, but a German guard launch stopped them. There were no serious repercussions for the apprehended persons and thus quite a few of the people that had been on board still succeeded in fleeing that same autumn. As they evacuated, the Germans took Alar to Germany but after the war, its owners, who had reached the West, managed to get the ship back and it has been preserved to this day.

Starting from 1998, it is back in its home at Sõru harbour.

Kui laev oli Kõrgessaare sadamas, varjas end selle pardal teadaolevalt Eesti ainuke „meremetsavend“, Lepiku külast pärit Arvid Saart. Arvid otsustas pärast sundteenimist nii Punaväes kui Saksa sõjaväes, et „aitab jamast“ ja jaanuarist märtsini 1944. a varjas ta end „Alaril“.

When the ship was at Kõrgessaare harbour, Arvid Saart from Lepiku hamlet, the only known ‘maritime forest brother’ in Estonia, was in hiding on board that ship. After being forced to serve in both the Red Army and the German Army, Arvid decided that he had had ‘enough of that nonsense’. He hid on board Alar from January to March of 1944.

Eesti põgenike purjekad „Kodu“, „Lübeck“, „Hiiu“, „Triina“, „Vello“ ja „Kristiine“ Rootsis Vikinghillis 28. mail 1945. aastal enne NSV Liidule üle andmist.

The sailboats Kodu, Lübeck, Hiiu, Triina, Vello, and Kristiine at Vikinghill in Sweden on 28 May 1945 before they were handed over to the Soviet Union.

Illustratsioon / illustration: GM

Septembri keskpaigas põgenemine intensiivistus veelgi. Hiiumaalt üritasid põgeneda nii hiidlased ise kui ka sajad mandrilt saabunud. Põgeneti nii väikeste paatidega kui ka suuremate alustega. Suurematest alustest lahkusid Hiiumaalt Rootsi näiteks purjekas „Enge“ umbes 500 inimesega pardal, mootorpurjekas „Hiiu“ umbes 100 inimesega, purjelaev „Munter“ umbes 150 inimesega.